WORLD WATCH--“Mr. Kim may be partly motivated by an intense need to roll back sanctions that, by all accounts, have begun to bite.”

Whoa and ouch. This was my wakeup paragraph. I was sitting at Starbucks, reading the New York Times, feeling confusing old emotions wash over me on the first day of the New Year, when suddenly these words hit me like a sucker punch: The sanctions against North Korea “have begun to bite”?

Compare this throw-away fragment of international news with a brief analysis of the effect of U.S. and global sanctions against North Korea by the Council on Foreign Relations: “Sanctions are often felt most by ordinary families, not the power elites who are the intended targets. . . . Sanctions and extended periods of drought have left many of North Korea’s twenty-five million people malnourished and impoverished.”

The wakeup bite for me wasn’t that the New York Times was wrong, simply that, as it presented the latest bit of international news to its global audience, the context of its reporting wasn’t factual data but 21st century mythology.

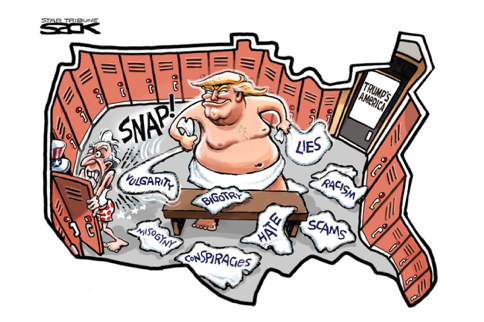

In our contemporary mythology, the defining gods, especially here in the “developed world,” are hulking, dangerous entities called nations, which stomp across the planet endlessly pursuing their interests. They are alleged to be conscious beings, usually with human faces — Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un — and their power rivals that of Zeus or Yahweh. But the effects of their behavior, even when it kills actual humans, is trivialized by the scribes as the equivalent, for instance, of a divine a bee sting.

Notice how quietly, how smoothly, most geopolitical reporting shifts back and forth between actual individuals and the imaginary beings called nations:

“The statement emphasized the roles of the two Koreas in resolving the nuclear crisis. President Trump, in contrast, has pursued a tougher approach . . .”

“But Mr. Moon also agrees with China and Russia that talks are needed to resolve the nuclear crisis. Mr. Kim’s sudden peace overture on Monday will probably encourage both Russia and China to renew their calls for some kind of ‘freeze for freeze’ — a freeze on North Korean tests in return for a freeze on all American-South Korean military exercises. Presumably, under that situation sanctions would begin to ease.”

OK. Nuclear freeze — very important. The Times story contained sober and responsible data, but I still felt tormented by it. Slowly it began occurring to me: The jargon here is mythical. And such reporting does nothing but perpetuate the status quo that keeps these belligerent, increasingly unstable gods in power.

In such a context, the only peace that’s possible is tense and temporary. To long for lasting, transcendent peace — to imagine that it’s possible — is to marginalize yourself. Come on. Read Trump’s latest tweet: “North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the ‘Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times.’ Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!”

The voice crying out is bigger than Donald Trump. It’s the voice of the mythical nation desperately shrieking: I’m not going away!

My response: Yes, you are.

The most toxic force on Planet Earth is nationalism. I’m not against collective consciousness. I believe with all my being in a human identity that transcends self and ego, but the concept of “the nation” is poisoned by the worst of who we are.

Addressing the question what is a nation, the Global Policy Forum explains: “National identity is typically based on shared culture, religion, history, language or ethnicity.” But they leave out the most important element. National identity of the Trump sort — and as quietly revered in the New York Times and the rest of the status quo media — requires a shared enemy. Without it, there’s no news.

A year ago, after Trump’s election, I suggested he may be the poster boy of nationalism’s last gasp, that a larger consciousness is waiting to lay claim on American politics.

“Trump says build a wall. Even if the wall is mostly a metaphor, the effect of that metaphor is to lock in consciousness, as though ‘America’ is the only truth Americans are capable of understanding: Fifty states and that’s it. We’re exceptional and the rest of you, keep out. Locked-in consciousness never keeps people safe, but it does keep them scared. You might call it patriotic absolutism, which yields fear, violence and war.”

The latest manifestation of the border wall is in relation to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the law protecting some 700,000+ people — a.k.a., “the dreamers” — born outside the U.S., brought here as children, which could expire in March. Trump says he won’t renew DACA unless he gets congressional approval for his lunatic wall, estimated to cost between $68 billion and $158 billion to build. “We need it. We see the drugs pouring into the country, we need the wall,” Trump said.

Besides the cost, there’s another overlooked detail: “Environmental groups have also expressed concerns over the potential impact of a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border,” according to Newsweek.

“Aside from the massive carbon footprint associated with the transport of raw materials, the U.S.-Mexico border is also home to many endangered species that routinely move between both sides of the Rio Bravo. The jaguar is one these species. As reported in Science earlier this year, the border wall would decimate the jaguar population across North America.”

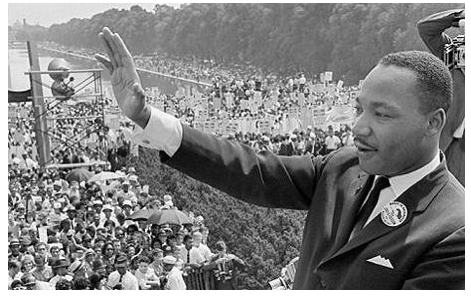

If only for the sake of the jaguar, it’s time to expand our consciousness, to create a myth called One Planet.

“You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one . . .”

(Robert Koehler is a contributor to CityWatch, courtesy of PeaceVoice. He is a Chicago award-winning journalist and editor.)

-cw