Comments

LA ARCHITECTURE -

Featuring a voice you know. And a story you don’t.

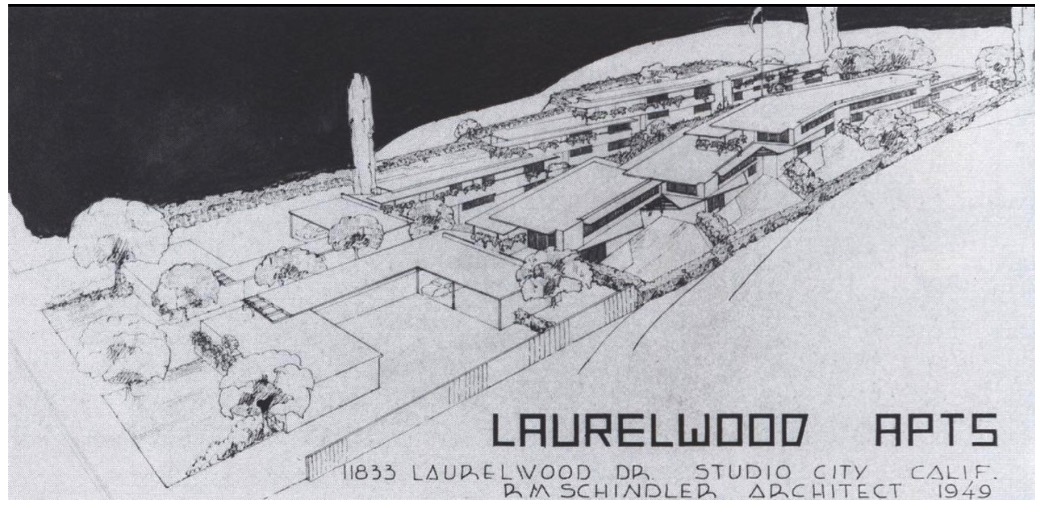

Around the corner from the Gold House, at 11833-37 Laurelwood Drive in Studio City, stands one of the finest modern expressions of the ubiquitous courtyard apartment complex to be found anywhere in Southern California. This 20-unit complex, built in 1949, was Rudolph Schindler’s last and largest multi-family design, a testament to his ability to reimagine communal living with his signature spatial flair.

Laurelwood Apts: Schindler’s 1949 masterpiece of communal space.

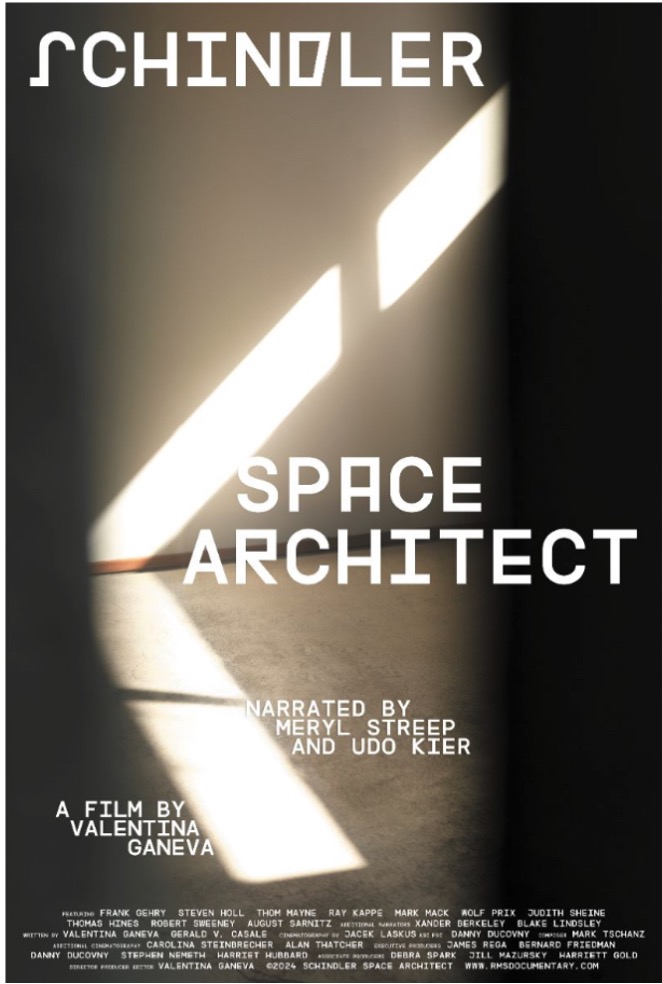

Disclosure: I’m a contributing producer on Schindler Space Architect, a documentary that explores the life and work of R.M. Schindler—and his singular vision of “Space Architecture.” It’s a film about Los Angeles as much as it is about architecture, and the creative tensions that shaped both.

They say don’t meet your heroes. I met mine every morning—barefoot, walking across the hardwood floors, leaning on the magnesite kitchen counter.

The cool touch of magnesite in the Gold House kitchen, a Schindler signature.

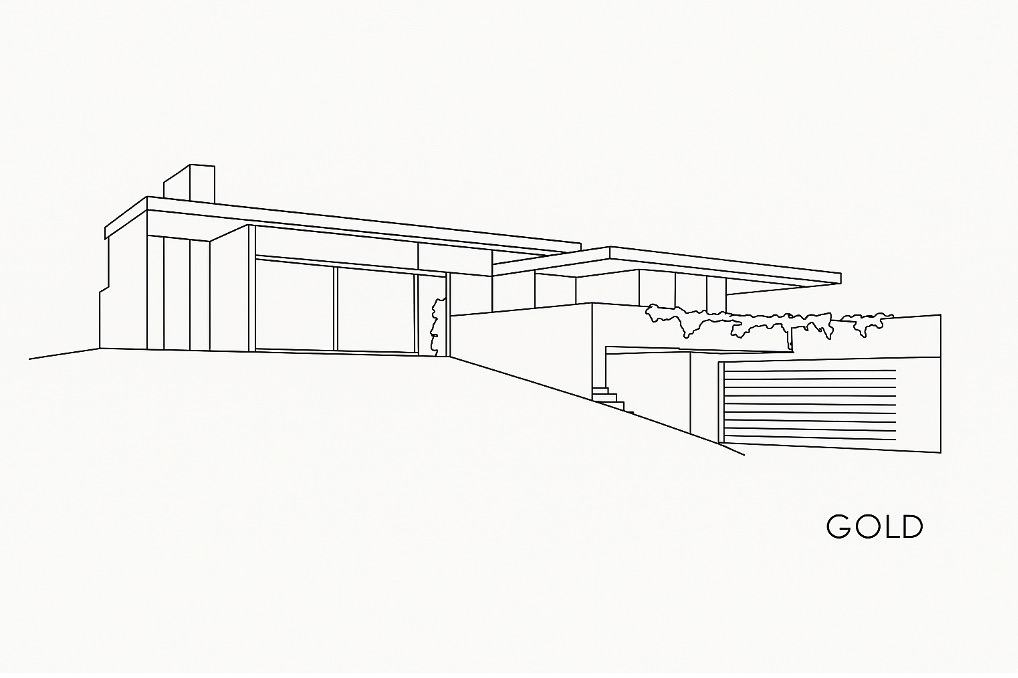

I live in a house designed by Rudolph Schindler. The “Gold House,” perched in the Studio City hills, is one of his later works—restorative, eccentric, cozy in its angles, and impossible to walk through without thinking, “Someone really designed this.” Which he did.

The Gold House in Studio City, where Schindler’s angles invite daily wonder.

Schindler was a provocateur who built to human scale. A European transplant who never left Los Angeles.

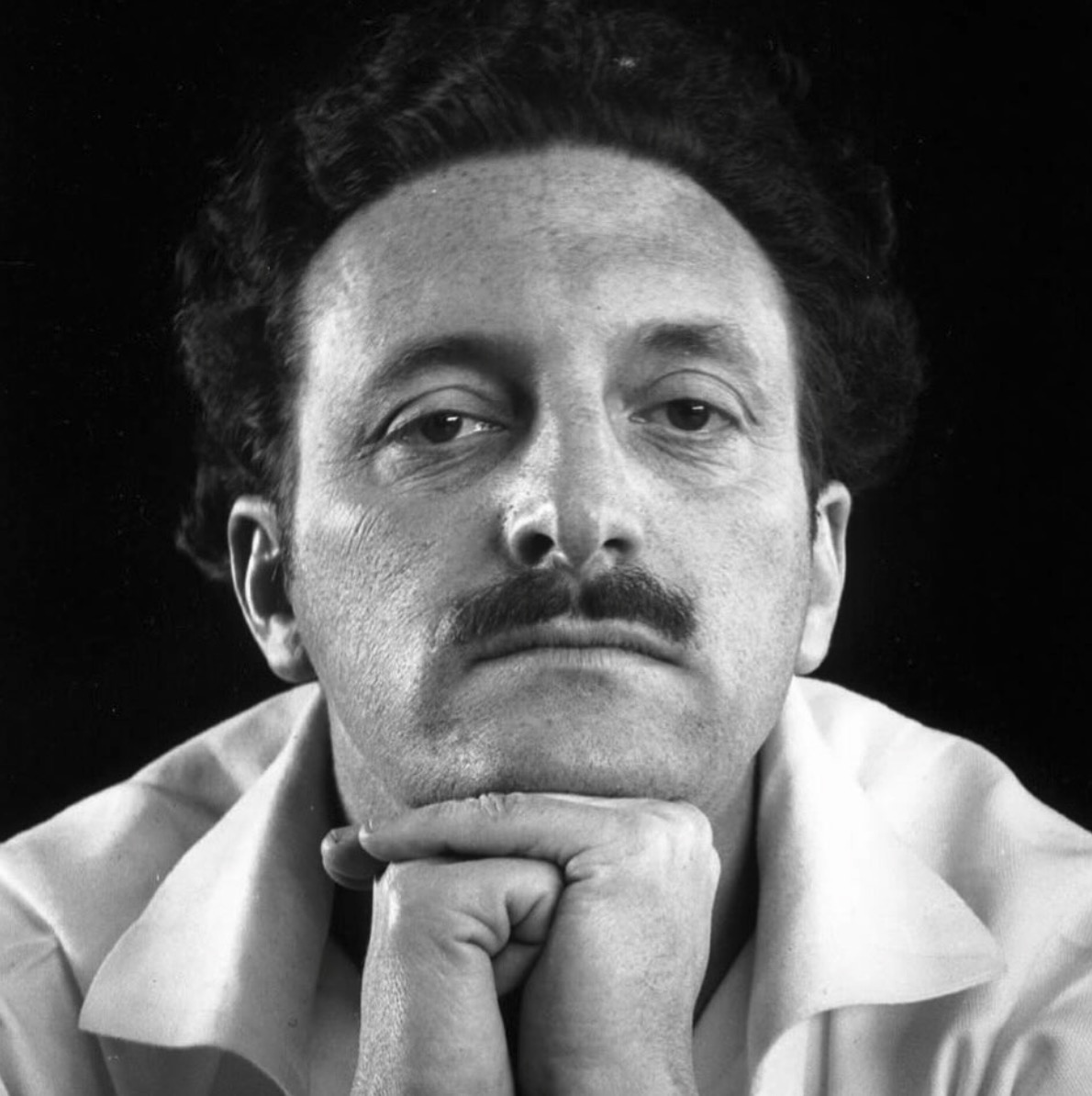

Rudolph Michael Schindler (1887–1953)

He drew lines not to show off, but to bring space alive. His homes whisper, some shout. They’re not declarations—they’re experiments that still resonate, a hundred years later.

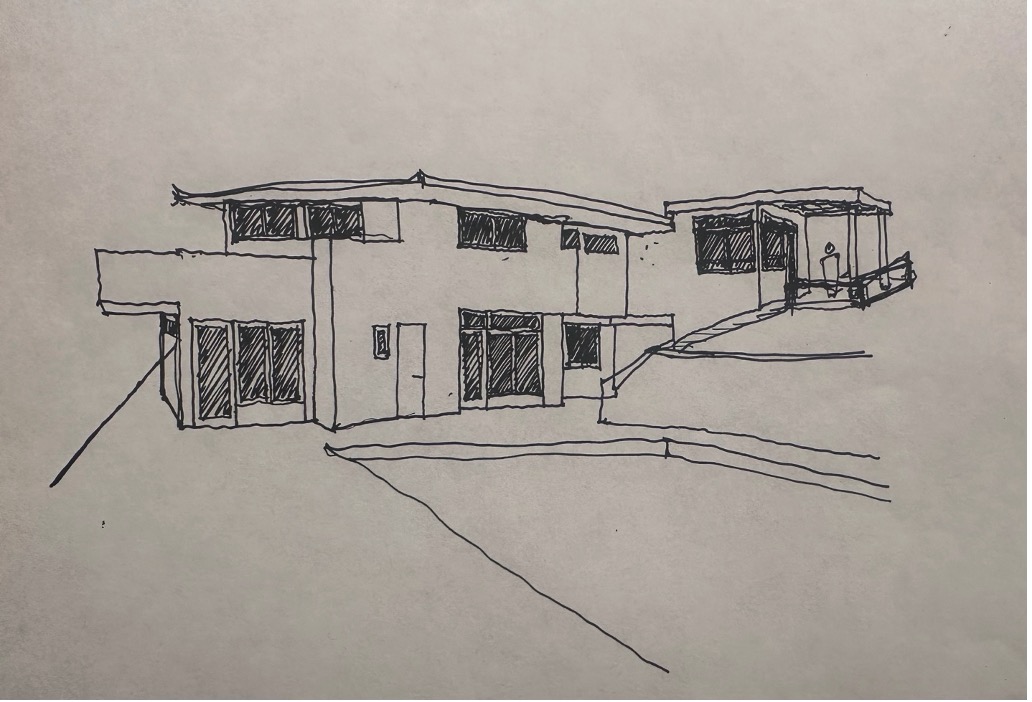

Schindler’s drawing of the Gold House, a blueprint for human-scale living.

Living in Schindler’s world made me curious about how others see him, so when I heard about a documentary called Schindler Space Architect, narrated by Meryl Streep with Udo Kier voicing the man himself, I thought: okay. Let’s see what we’ve got here.

Schindler Space Architect at Laemmle Santa Monica, November 7–13, 2025. Join the journey. #FYC or #ForYourConsideration

A Familiar House, A Strange Voice

This is the part where I admit I’m biased. I’ve lived in a Schindler for decades. My good friends Chris Culliton and Amy Schulenberg live in another—what we call the Pressburger House. And Susan Orlean, the great author of Joyride (and yes, a Michigan grad like Chris and I, who were roommates in Ann Arbor), lives in yet another: the Kallis House. So yes, three Michigan grads, three Schindler houses. Not a cult—just a coincidence. Or maybe, as Valentina Ganeva, the documentary’s director, would say, a “meaningful” one.

Studio City Schindler houses are disproportionately owned by UofM graduates. Go Blue!

How Meryl Streep Ended Up Voicing a Film About a Radical Austrian Architect

During the pandemic, Valentina Ganeva, director of Schindler Space Architect, found herself deep in conversation with a professor from upstate New York who had reached out because of an uncanny moment in the story: the real-life coincidence that R.M. Schindler and Richard Neutra, once close collaborators and later rivals, ended up side by side in the same Los Angeles hospital near the end of their lives. That bit of cosmic symmetry was too good to ignore, and the professor, researching uncanny coincidences, wanted to know more.

The two hit it off over Zoom, talking ideas and improbabilities. Eventually, the professor asked, almost offhandedly, “Who’s narrating your film?” Ganeva replied that she’d tried reaching out to Anjelica Huston but joked that “nobody gets back to anybody.” “Well,” the professor said, “I may know someone who knows someone.”

Shadows across the Gold House, a living experiment in Schindler’s vision.

That “someone” was possibly connected to both Meryl Streep—through a student or mentorship relationship—and director David Frankel (The Devil Wears Prada).

By some cosmic fluke, the material reached Streep, and she said yes. Perhaps she felt a tug of her own—after all, she had portrayed Susan Orlean in Adaptation, and Orlean lives in Schindler’s Kallis House, just blocks from the Roth House she and her husband also once owned. (Both Schindler homes. Both deeply L.A. stories.) Or maybe she loved the material.

Ganeva was stunned—and the voice that brought Virginia Woolf, Margaret Thatcher, and Julia Child to life would now speak for Schindler. Coincidence circle: complete.

The film is elegant, elliptical, like wandering through one of Schindler’s houses—no tour guide, no velvet rope, no clear exit.

The Gold House stoop, an invitation to step into Schindler’s world.

It doesn’t aim for objectivity; it gives you Schindler’s voice (via Kier), his lovers and collaborators, his buildings, and his restlessness. It’s not a greatest-hits rundown but a personal drift through his world.

On Being Yourself

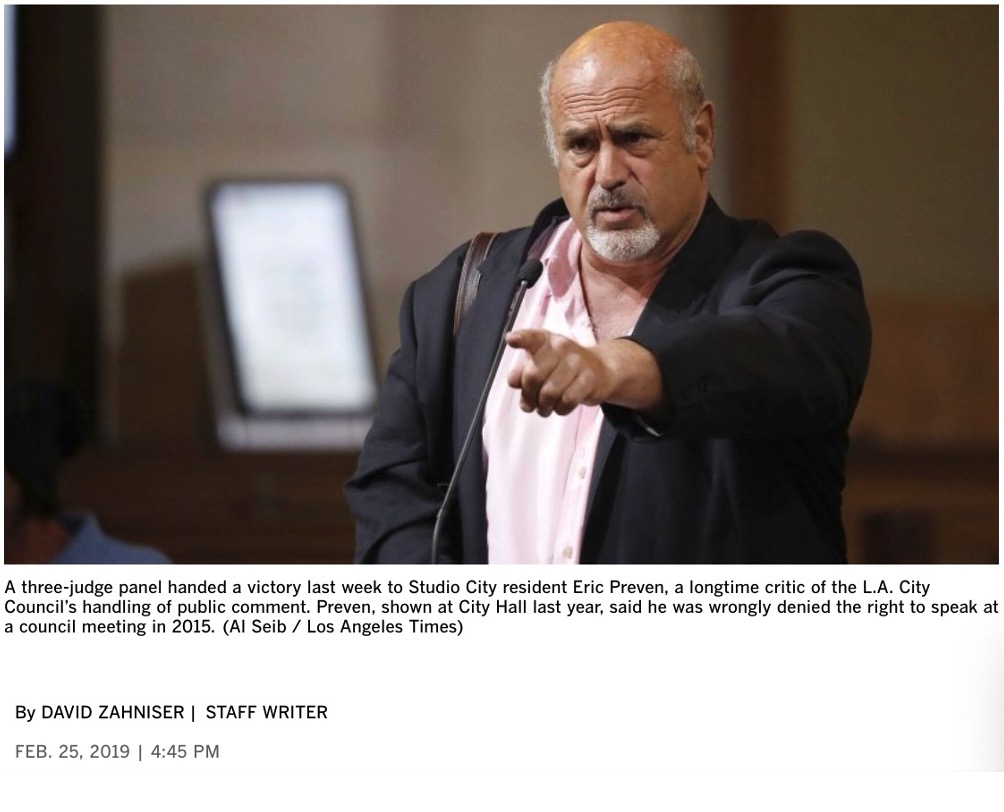

Schindler was never trying to be the best. He was trying to be himself. That’s the idea that comes across strongest in the film—and the one I try to live by, as a writer-producer, advocate, watchdog, and guy who’s spent more time than I care to admit in City Hall chambers and public comment queues.

Eric Preven, watchdog embodies the spirit of Schindler’s defiance.

You could call it “docenting” in another register. Speaking up for spaces that matter. Not just the ones with landmark plaques, but the ones with stories.

Schindler’s buildings are easy to mythologize. But they’re not for everyone. The flat roof might leak. The cantilevered deck might sag. The hallway might be just a little too narrow, like it’s challenging you to pass through. These aren’t flaws—they’re the point. The buildings ask you to notice. To consider. To reflect.

That’s why I loved Jacek Laskus’s cinematography—so tactile you could feel the grain of the wood, the dryness of the plaster, the coolness of the shade.

Gold House at night.

And Danny Duchovny, who also executive produced, let the film linger in that space between reverence and strangeness. In and out of focus, through a single lens reflex.

In my head, Schindler’s voice sounds like Roland Kuster, a Swiss-German artist who once told me, “Don’t imitate. Translate.” That’s Schindler’s mantra too.

La Super-Rica, Tantara, and Tangents

Am I digressing? Probably. But that’s the point. This isn’t a write-up. It’s a walk-through.

I once drove back from Santa Barbara with a bottle of Tantara Pinot Noir, a gift for a woman in Schindler’s Ellen Janson house on Skyline Drive, where I arrived at “Skyhooks” with wine and questions. Somehow, this is always how it goes with Schindler: you start with a building and end up somewhere personal.

My former wife and I dug into Schindler’s papers at UCSB and shared the Gold House for MOCA’s 2001 exhibit, opening it to the public more than once.

An Elisa Rooks working drawing from 1999 Gold House renovation.

Over time, I started to see the architecture as just one part of a larger, messier, deeply human story.

Like his 1920s letter to Aline Barnsdall, in which he defends the contractors Long and Watt. They had underbid the roofing job at Hollyhock House, then stuck with it as material prices and scope changed. They were losing money, and Schindler could’ve stayed quiet. Instead, he wrote: “They have proven to be gentlemen... Alteration jobs are the dread of any estimator and if both the building and the addition are of a new and unusual nature, the estimate becomes a mere guess. The only fair way to do such work is on a “cost” or “unit” basis."

And then, this:

“We clamor for peace between nations. Should we not start by overcoming our instinct of warlike attitude in our private life?”

Schindler wasn’t just an architect. He was a humanist. Even in construction disputes, he urged empathy over conflict.

Not always, of course.

In his correspondence with Joseph George Gold—the very client who commissioned the house I now live in—Schindler took a different tack. Fed up with unpaid bills and endless change orders, he dropped the pleasantries: “If you really think that the issue of our arguments [is] a ‘few paltry dollars,’ I can’t see why you spent all this time writing instead of just paying them.”

The line is blunt. Dagger-like. And totally earned. Schindler didn’t tolerate disrespect, even from the wealthy.

Find Something Worth Fighting For

At 30, Rudolph Schindler upended his life to work for Frank Lloyd Wright in 1917, captivated by the master’s vision. When Wright left for Japan to design the Imperial Hotel, he entrusted Schindler with the Hollyhock House project—a bold vote of confidence. But Wright’s praise was backhanded. He called Schindler a “patient assistant” whose talents were “adequate” to his demands, yet always “aware of the significance” of Wright’s work. Adequate? If there’s a more arrogant way to say something nice, I’d love to hear it.

That tension—admiration mixed with defiance—drove Schindler to keep building, quirks and all. It’s a reminder: find something worth fighting for, even if it’s messy. Whether you’re at a city council meeting, in a writing room, or a dinner party where someone trashes modernism, stake your ground.

Schindler did. He quarreled with clients, ruffled peers, and got left off lists. But he kept going. Being Schindler is about forging a life aligned with your principles. Drawing the lines that matter. And, if you’re lucky, living inside them.

The film’s charm is its unpolished intimacy, like a conversation with Schindler’s devotees. It’s less a polished essay than a reminder that architecture isn’t just about buildings—it’s about the people who keep them alive.

The Gold House glowing with Schindler’s restless spirit.

If you’re in LA, don’t miss Schindler Space Architect at the Laemmle in Santa Monica, November 7–13. Screenings on Saturday, Nov. 8 to be followed by Q&A with Valentina Ganeva, director/producer and special guests. For Your Consideration - Best Documentary Feature and Best Original Score. Visit http://www.rmsdocumentary.com/ for details. #FYC #RMSdocumentary #SchindlerSpaceArchitect #FrankGehry #ThomMayne #StevenHoll #RayKappe #MarkMack #ModernArchitecture

Eric Preven is the "head docent" at the 1946 Gold House designed by R.M. Schindler. And he does other stuff too.

Additional Schindler Angles on CityWatchLA

Summer Funk and Lots of Other Thoughts — August 11, 2021

https://www.citywatchla.com/los-angeles/21918-summer-funk-and-lots-of-other-thoughts

Barnsdall/Hollyhock notes, Schindler’s 1929 roofing-contractor letter, a 1940 defense of modern design, and my own Schindler restoration thread.

Friday the 13th at LA’s Budget Hearing — May 15, 2022

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/24594-friday-the-13th-at-la-s-budget-hearing

Schindler House centennial (MAK Center), and lore from associates about frustrations and romance during a 1940 build.

Refunding Ticketmaster — July 3, 2023

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/27215-refunding-ticketmaster

A Pauline Gibling Schindler cameo in a media/arts riff.

Give Me Something Larger — July 31, 2023

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/27358-give-me-something-larger

Living in a Schindler (Gold House), the 1932 MoMA snub, and a 1947 Gold House defense.

La Super-Rica — July 27, 2023

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/27347-la-super-rica

Gold House restoration + Ellen Janson letters leading to “Skyhooks.”

LA City Council Parody — August 10, 2023

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/27424-la-city-council-parody

A 1925 R.M. Schindler → Aline Barnsdall beeswax letter excerpt.

One Percent Inspiration — September 4, 2023

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/27542-one-percent-inspiration

Schindler’s 1929 “Long & Watt” letter and 1946 Lester Horton letter, quoted at length.

Mabuhay — October 5, 2023

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/27725-mabuhay

Barnsdall/Hollyhock context with a Schindler note in a City Hall dispatch.

Red Flag Fatigue — September 16, 2024

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/29555-red-flag-fatigue

“If you can afford to restore a bloody Schindler…”—a blunt line about preservation and taxes.

Curated Chaos — November 11, 2024

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/29862-curated-chaos

A brisk Schindler mini-bio (Loos → Wright → Barnsdall) folded into a Veterans Day meditation.

Tip Your Officeholders — December 26, 2024

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/30078-tip-your-officeholders

Calls out the SCHINDLER SPACE ARCHITECT documentary and your producer credit.

The End of the World as We Know It — January 9, 2025

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/30155-the-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it

Palm Springs screening shout-out for Schindler Space Architect amid fire/weather notes.

Smart Speaker On Broadway — May 15, 2025

https://www.citywatchla.com/eric-preven-s-notebook/30887-smart-speaker-on-broadway

The tongue-in-cheek “Schindler Award for Culinary Excellence” and a Gold House nod.

(Eric Preven is a Studio City-based television writer-producer, award-winning journalist, and longtime community activist. He is known for his sharp commentary on transparency and accountability in local government. Eric successfully brought and won two landmark open government cases in California, reinforcing the public’s right to know. A regular contributor to CityWatch, he combines investigative insight with grassroots advocacy to shine a light on civic issues across Los Angeles.)