Comments

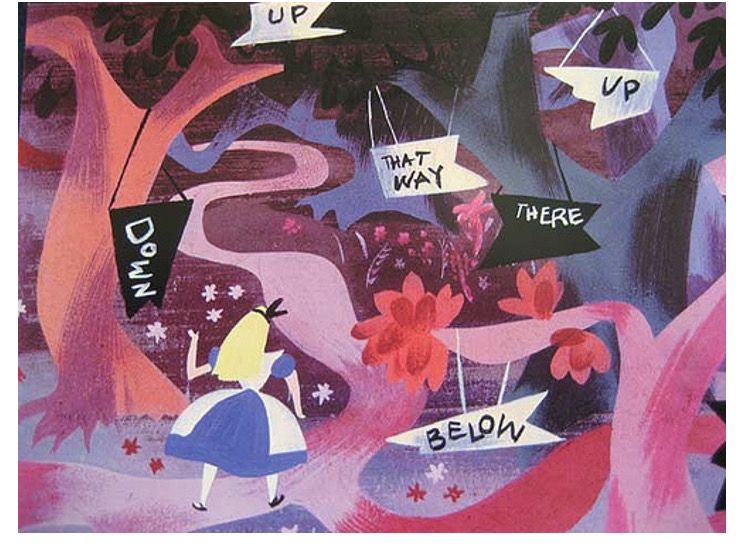

UNHOUSED - “It's how I learned the real world doesn't always adhere to logic. Sometimes down is up, sometimes up is down.” Lewis Carrol, Alice in Wonderland

When I started to read Mayor Bass’ emergency declaration, I was hopeful a leader finally understood the magnitude of the homelessness crisis. The first four of its six pages list the consequences of years of failed intervention programs. They are a litany of the tragic results of the City and County’s inadequate response to the crisis, including:

- An increase of 238 percent in the number of unhoused families since 2007.

- The number of unsheltered people in L.A is 18 times higher than that of New York, as a percentage of population.

- Recognition that at least half (and likely much more) of the unsheltered population suffer from mental and/or substance abuse problems.

- Fires attributed to homeless camps tripled between 2018 and 2021, averaging 24 per day.

- And, in what should be the mea culpa recognizing the failure of current programs to address the crisis, the declaration states: “The City of Los Angeles has responded to the rapid increase in its homeless population with unprecedented investments into homelessness solutions, including a nearly $1.2 billion commitment in the 2022-2023 City budget for the construction of thousands of units of supportive housing, the expansion of bridge housing, and the hiring of professionals to address the homelessness crisis and, notwithstanding these efforts, the number of those experiencing homelessness in the City continues to increase and outstrip the resources and services that the City has provided.”

After reading the previous paragraph, one would think the next statement would be something like: “We recognize our past interventions and programs have not worked. Therefore, I am ordering all involved departments to reassess their homeless response and return to me within 30 days with a plan to address the root causes of this crisis, and to set measurable goals for permanently reducing the homeless population by xx% withing the next 12 months. Programs and their managers, and service providers, will be evaluated solely on their progress toward the reduction goal. Any program shown to be ineffective or inefficient will be restructured or eliminated.”

Instead, the declaration includes vague directives like:

- Regulatory relief from other jurisdictions and within Los Angeles City agencies to create flexibility to address the crisis;

- Relaxation in the restraints that limit the ability of the City’s proprietary departments to create flexibility to address the crisis;

- Increased housing placements;

- Increased starts on new affordable housing options;

- An increase in temporary and permanent housing units.

There is no mention of measurable goals or who will be doing what. Even worse, the declaration heavily promotes housing as the primary solution to the crisis, with only secondary mention of mental health and substance abuse interventions, except for a grammatically tortured sentence: “Increased outside aid through access to mental health and substance use beds.”

In other words, “We know what we’ve been doing hasn’t worked. So, we’re going to keep doing it, but even more.” What’s really interesting here is how Bass and the advocates advising her at once recognize the root causes of homelessness, then choose to ignore them in the same breath. Truly, logic worthy of a Lewis Carrol character.

Bass’s directive cites the true causes of homelessness, and they aren’t related to housing: the ready availability of fentanyl and other drugs, and untreated mental health conditions. Then her action plan conveniently ignores these issues, pushing them to a brief mention buried in a list of “Housing First” solutions.

Much like the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland, what Bass says in the emergency declaration and what she says in other situations are quite the opposite. The declaration says the unsheltered are far more likely to be victims of violent crime, (especially women). The declaration cites the frequency of fires in encampments: the LAFD says 54 percent of all fires can be attributed to homeless camps. By publishing these statements, one would think Mayor Bass realizes encampments are the source of incredible human misery. Yet, responding to a reporter in a March 19 L.A. Times article on Inside Safe, “Bass said encampments are ‘small communities’ that serve as support systems for their inhabitants. Spreading people from the same encampment across three different hotels is ‘not what I want to see happen,’ she said.” Perhaps someone should have reminded her of the four people who died in the Echo Park tent “community”, including an 18-year-old girl who died from an overdose.

The widespread problem of substance abuse and mental illness has been recognized as the primary cause of declining Metro line ridership. Yet, somehow, the same problems that plague Metro, and drove the Skid Row Housing Trust to bankruptcy aren’t the same problems at the root of chronic homelessness. When confronted with the fact that mental illness and substance abuse are common among the unhoused, advocates have ready-made responses, usually along the lines that homelessness itself causes people to descend into drug abuse and mental illness. Many professional studies, however, say substance abuse often starts the downward spiral, by first causing job loss, and therefore loss of housing. While being homeless can drive one to substance abuse, it doesn’t change the fact that at least half the homeless have chronic mental health or substance abuse problems, (LAHSA, which is notorious for underreporting homeless issues, puts the percentage at 41 percent, while a more professional UCLA study puts it closer to 75 percent). Continued abuse makes it far more difficult to regain meaningful employment, and therefore housing. Living in the stressful environment of the streets for prolonged periods can be a major contributor to mental issues.

If the primary causes/consequences of homelessness are substance abuse and mental illness, one would think the main pillars of a homelessness intervention program would be preventing and treating those causes. However, building such a program would deny the primary premise of Housing First, which emphasizes construction and placing people in housing without any commitment to treatment. This approach is a bit like rebuilding a house while it’s still on fire. It makes far more sense to extinguish the fire and then think about rebuilding.

Despite the emergency declaration’s mention of key performance indicators, Inside Safe holds service providers to no actual performance measures, as in previous open-ended contracts. The declaration does little more than offer another—and even easier--opportunity for non-profits to continue running up titanic bills while producing little in actual results. Indeed, the agencies can’t even meet one of Mayor Bass’s priorities by keeping people from the same encampment in the same shelter. Despite her view that encampments are “communities”, a March 19 L.A. Times article described how many unhoused people have been shuffled from one motel to another in an effort to keep them housed. Moving people among districts violates the agreement that was part of last year’s settlement between the City, County and the L.A. Alliance for Human Rights; that agreement requires each Council District to identify housing for at least 60 percent of the homeless in the district. Apparently, even federal lawsuits must bow to bureaucratic fumbling that has become endemic in local homelessness response.

Indeed there is evidence Inside Safe harms the working poor, who make up a sizable portion of the homeless who don’t need medical or mental interventions. This article in the California Globe describes the effect moving people from one shelter to another has on those who have, or are trying to find, jobs.

Inside Safe had the potential to fundamentally change the way Los Angeles has responded to homelessness. Mayor Bass could have used her emergency powers to restructure homelessness relief to be focused on the goal of getting people off the streets and into the supportive care they need. She could have made service providers accountable for results instead of merely racking up contact hours building “relationships” with the unhoused. She could have emphasized services over building overpriced housing. Instead, she merely ensured the same failed policies, using the same under-performing providers, addressing the wrong priorities, will continue, and in most cases, increase.

Truly, of Inside Safe, and the City’s homeless policy in general, Karen Bass could say “"But that's just the trouble with me. I give myself very good advice, but I very seldom follow it."

(Tim Campbell is a resident of Westchester who spent a career in the public service and managed a municipal performance audit program. He focuses on outcomes instead of process. The opinions expressed by Tim Campbell are not necessarily those of CityWatchLA.com.)