For California … and America … Common Sense on Immigration

NEW GEOGRAPHY--No issue divides the United States more than immigration. Many Americans are resentful of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants, worry about their own job security, and fear the arrival of more refugees from Islamic countries could pose the greatest terrorist threat. At the other end of the spectrum are those who believe the welcoming words on the Statue of Liberty represent a national value that supersedes traditional norms of citizenship and national culture.

What has been largely missing has been a sharp focus on the purpose of immigration. In the past, immigration was critical in meeting the demographic and economic needs of a rapidly growing nation. Simply put, the country required lots of bodies to develop its vast expanses of land and natural resources and to work in its factories.

The need for foreign workers remains important, but the conditions have changed. No longer a largely rural, empty country, more than 80 percent of Americans cluster in urban and suburban areas. Many routine jobs have been automated; factories, farms and offices function more efficiently with smaller workforces. Since at least 2000, notes demographer Nicholas Eberstadt, the “Great American Escalator” has stopped working.

These changes suggest the need to rethink national immigration policies. In a country where wages for the poorest workers have been dropping for decades and incomes have stagnated for the middle class, allowing large numbers of even poorer people into the country seems more burden than balm. They often work hard, but largely in low-income service jobs and in the low end of the health care field. In California, home to an estimated 2.7 million largely Latino undocumented immigrants, approximately three in four Latino non-citizens struggle to make ends meet, as do about half of naturalized Latino citizens, according to a recent United Way study.

Overall, our current immigrants, legal and illegal, have not advanced as quickly as in previous generations. This, along with the crisis in much of Middle America, should be our primary national concern. This doesn’t necessarily translate to mass deportations or even severe cutbacks in legal immigration, as some, including Attorney General Jeff Sessions and several congressional Republicans, have said. But it certainly does suggest taking a fresh look at how we view immigration.

Learning From Abroad

So, what kind of immigration is best for America?

Models to consider are those that put premiums on marketable skills and language proficiency rather than family reunification. The Canadian and Australian systems, as President Trump correctly noted, are more attuned to their own national needs, compared with the U.S approach, which emphasizes family re-unification. Canadian authorities allow some 60 to 70 percent of their immigrants to come for economic purposes, notes Carter Labor Secretary Ray Marshall, supporting their system mainly by “filling vacancies that are measured and demonstrated in the Canadian economy.”

Such a needs-based program would be a better, and fairer, way of addressing skills shortages than the odious H-IB program, which allows temporary indentured tech workers to replace American citizens. Instead, talented newcomers would be welcomed as future citizens and given the right to negotiate their own labor rates and conditions.

This emphasis on admitting immigrants with needed skills leaves Canadians and Australians with generally more positive views about immigration than Americans. Australia is one of only three countries in the world where children of migrants do better at school than children of non-migrants. Canadian support for immigration is particularly high in Toronto, which has been transformed from a sleepy Anglo enclave to a vibrant, diverse global capital.

But such hospitality is not limitless. A former Canadian immigration judge told me recently, in a tone of alarm, that his country’s invitation to 25,000 Syrian refugees could incubate the same sort of disorder that we see across Europe. There, in many heavily immigrant communities, poverty and isolation has persisted, sometimes for generations.

I doubt many Americans would want to see the kind of social unrest we see across once peaceful places like Sweden, where women now complain of being perpetually harassed, even as supposedly feminist politicians look the other way. In France, Muslims make up about 7.5 percent of the French population compared to 1 percent in the U.S., but France has been ravaged by Islamic terrorism, Muslim-fueled anti-Semitism, and a widening cultural gap between the immigrants and the indigenous French population. In France and many other European countries, we see the rise of nativist politicians that make Donald Trump seem like Mother Theresa.

Citizenship and National Culture

The United States could be headed to a similar devolution. America’s ideals may be universal, but our political community has always been based on U.S. citizenship. You should not have to be an Anglo to admire the Founders, or to embrace the importance of the Constitution. Yet it’s now fashionable among some progressive activists to reject established American political traditions, which constitute a fundamental reason people have come here for the last two centuries.

Yet the “open borders” lobby on the progressive left increasingly demeans the very idea of citizenship. In some cases, they see immigration as way to achieve their desired end of “white America.” Some advocates for the undocumented, such as Jorge Bonilla of Univision, assert that America is “our county, not theirs” referring to Trump supporters. Others, like New York Mayor Bill di Blasio, refuse to differentiate between legal and illegal immigrants.

As usual, California leads the lunacy. Gov. Jerry Brown, who famously laid out a “welcome” sign to Mexican illegal and legal immigrants, has also given them drivers’ licenses and provides financial aid for college, even while cutting aid for middle-class residents. Some Sacramento lawmakers are pressing to give undocumented immigrants’ access to state health insurance. Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de Leon recently boasted, “Half of my family would be eligible for deportation under the executive order, because they got a false Social Security card, they got a false identification.”

The “open borders” ideology has reached its apotheosis in “sanctuary” cities which extend legal protection from deportation to criminal aliens, including those who have committed felonies. Donald Trump opportunistically emphasized this absurd and inappropriate situation—sometimes invoking the names of murdered Americans—during his 2016 campaign. The only mystery is why it would surprise the chattering class that many voters responded to his message.

Most Americans are more practical about immigration than politicians in either party. The vast majority of us, including Republicans, oppose massive deportations of undocumented individuals with no serious criminal record. Limiting Muslim immigration appeals to barely half of Americans. Only a minority favor Trump’s famous “big beautiful wall” on the Mexico-U.S. border.

Yet even in California, three-quarters of the population, according to a recent U.C.-Berkeley survey, oppose “sanctuary cities.” Overall, more Americans favor less immigration than more. According to a recent Pew study, most also generally approve tougher border controls and increased deportations. They also want newcomers to come legally and learn English, notes Gallup. This is not just an Anglo issue. In Texas, by some accounts roughly one-third of all Latino voters supported Trump.

Sadly, immigration as an issue has been totally politicized. Obama deported far more undocumented aliens than his Republican predecessor, or any previous president, for that matter, without inciting mass hysteria. To be sure, Republicans face severe challenges with new generations that are more heavily Latino and Asian and generally more positive about immigration. The undocumented account for roughly one in five Mexicans and upwards of half of those from Central American countries, meaning that overly brutal approaches to their residency would be eventual political suicide for Republicans in many key states, including Arizona, Florida, Nevada, Colorado and even Georgia.

Any new immigration policy has to be widely acceptable -- both where immigrants are common as well as those generally less diverse areas where opposition to immigration is strongest. Unlike many issues, immigration cannot be devolved to local areas to accommodate differing cultural climates; it is, and will remain, a federal issue. A policy that melds a skills-based orientation, compassion, strong border enforcement, expulsion of criminals, and forcing the undocumented to the back of the citizenship line seems eminently fair.

Economic Growth: The Secret Sauce of Immigration Policy

Strong, broad-based economic growth remains the key to making immigration work. A weak economy, unemployment, population density, or sudden uncontrolled surges in migration, notes a recent Economic Policy Institute, drives most anti-immigration sentiment. The labor-backed think tank suggests it would be far better to bring in migrants with skills that are in short supply and avoid temporary workers, such as H-1B visa holders, who are paid lower wages, undercutting the employment prospects for Americans.

Given the demands of competition and changes in technology, it seems foolish to allow many additional lower-skilled people enter our country. This is not elitism: Industry needs machinists, carpenters and nurses as well as computer programmers and biomedical engineers. What we don’t need to do is flood the bottom of the labor market. Again, this reality is race-neutral. Economist George Borjas suggests that the influx of low-skilled, poorly educated immigrants has reduced wages for our indigenous poor, particularly African-Americans, but also for the recent waves of immigrants, including Mexican Americans, over the past three decades.

Like most high-income countries, America’s fertility rate is below that needed to replace the current generation. This constitutes one rationale for continued legal immigration. But our demographic shortcomings are also entwined with lack of economic opportunity, crippling student debt, and the high cost of family-friendly housing stock. In other words, one reason Millennials are putting off having children is because they can’t afford them.

Overall immigration is a net benefit, if the economic conditions are right. An overly broad cutback in immigration would deprive the country of the labor of millions of hard-working people, many of whom are highly entrepreneurial. The foreign-born, notes the Kaufmann Foundation, are also twice as likely to start a business as native-born Americans. It’s always been thus—and these aren’t just small, ethnic, family-owned restaurants we’re talking about. More than 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies were founded by immigrants or their offspring.

American immigration has succeeded in the past largely due to economic expansion. The historical lesson is clear: a growing economy, more wealth and opportunity, as well as a sensible policy, are the true prerequisites for the successful integration of newcomers into our society.

(Joel Kotkin is executive editor of New Geography … where this analysis was first posted. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. He lives in Orange County, CA.)

-cw

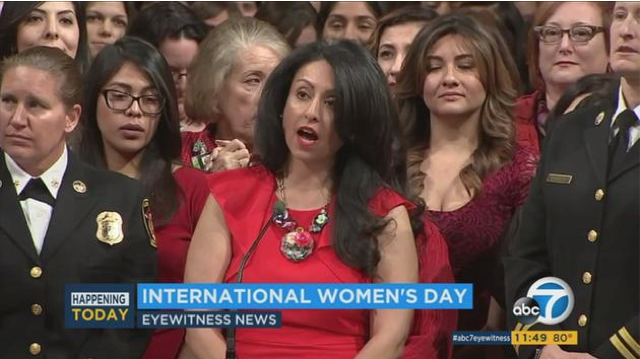

Women were encouraged to show support in one or more of three ways – to take the day off of paid or unpaid labor, to avoid shopping for one day (with the exception of small women- and minority-owned businesses, and/or to wear red in solidarity with A Day Without A Woman.

Women were encouraged to show support in one or more of three ways – to take the day off of paid or unpaid labor, to avoid shopping for one day (with the exception of small women- and minority-owned businesses, and/or to wear red in solidarity with A Day Without A Woman.

The second major area where school kids can interact with the homeless population just happens to be in the

The second major area where school kids can interact with the homeless population just happens to be in the

On Thursday, Garcetti again proposed a vague plan without any deadline for updating the long-stalled Community Plans. He finally signed an Executive Directive enacting a very limited reduction in "ex parte," or backroom meetings, aimed solely at his Planning Commission — and only after a developer formally files an application to get around zoning rules, an action that often happens long after numerous backroom meetings.

On Thursday, Garcetti again proposed a vague plan without any deadline for updating the long-stalled Community Plans. He finally signed an Executive Directive enacting a very limited reduction in "ex parte," or backroom meetings, aimed solely at his Planning Commission — and only after a developer formally files an application to get around zoning rules, an action that often happens long after numerous backroom meetings.

(Photo: Fernando Hurtado and his wife, Amy Areli, with two of their four children at St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.)

(Photo: Fernando Hurtado and his wife, Amy Areli, with two of their four children at St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.)  (Photo: Jim Mangia, President and CEO of St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.)

(Photo: Jim Mangia, President and CEO of St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.)

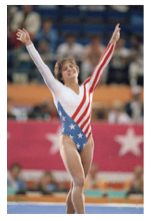

(Photo left: Mary Lou Retton celebrates her balance beam score at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Retton, 16, became the first American woman ever to win an individual Olympic gold medal in gymnastics. Photo by Lionel Cironneau/Associated Press.)

(Photo left: Mary Lou Retton celebrates her balance beam score at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Retton, 16, became the first American woman ever to win an individual Olympic gold medal in gymnastics. Photo by Lionel Cironneau/Associated Press.)

Visit the

Visit the