Shall We Wait for the Next Dam to Overflow? Vote YES on Measure S!

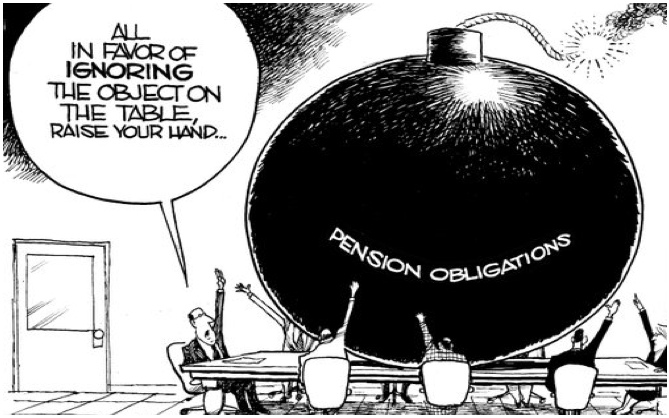

ALPERN AT LARGE--Planning and Transportation is NOT an issue for sissies in the Golden State, and particularly in the City of the Angels. This state, and this city, have been led by those fighting a "War on Math" for decades, and have found it easier to attack those decrying this "War on Math" than to confront it like adults.

Still confused about Measure S? I don't blame you. Yet Measure S is still the best way to bring the adults back to City Hall:

1) First, know when to get over national/politically partisan leanings.

Among my own family and friends, I've got members who are zealously pro-Trump, and others who are zealously anti-Trump. I'm personally zealous towards each expressing their views, because they each have a point or two to make--but there will have to be times when we have to focus on the objective, not subjective, issues surrounding Transportation, Infrastructure, and Planning.

In short, we've got too many people clustered in too dense a coastline, with respect to our infrastructure.

That isn't a "hater's declaration" but rather a statement that we're in trouble.

The Oroville Dam is one case where Governor Jerry Brown is having to ask political nemesis President Donald Trump for help. And with the understanding that as many people statewide and nationwide have problems even saying "President Trump" as they do "Governor Brown", we need to focus on our water problems.

We're asked to reduce water consumption while being told to allow more megadevelopments. In other words, we're supposed to consume and use less water to help the developers make more money?

Why are we not focusing on making sure we keep our water, and direct our water, to ensure the water supply for residents, for farmers, and even to allow the restoration of the Salton Sea?

Love him or hate him, President Trump is our nation's 45th President. Governor Brown is our governor. And we all should consider the reality that the Trump Administration has designated a proposed Huntington Beach desalination plant as one of the top 50 infrastructure projects for our nation to fund and prioritize.

No one says you have to like our President, or our Governor, but we all have to know when to shut up and work with them.

2) Second, know when to get over local/politically partisan leanings.

To suggest that Los Angeles is a city dominated by Democratic politics is to suggest that gravity makes things fall down when they aren't lifted up or supported. It's our reality, and either a good thing or a bad thing, depending on who you ask. Yet there are conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans in our town, and Measure S is NOT a partisan issue.

Both sides of the Measure S issue claim the other side is like Trump. Of course, that's prima facie reaching for your heart or your gut to make you decide who's "good" or who's "bad".

Particularly when we've got "environmentally-friendly" City Council members opposing Measure S while supporting development that's trashing and thrashing our environment.

Too much density + Not enough water + Not enough affordable housing + Not enough infrastructure = Pollution + Decreased air quality + Worsened congestion = Decreased Quality of Life.

Yes, Richard Riordan supports Measure S, but also established our Neighborhood Councils and supports local/grassroots empowerment. He's a Republican...but he's on the same side as:

U.S. congresswoman Diane Watson, Homeless Advocate Reverend Alice Callaghan, the Ballona Wetlands Institute, Damien Goodmon of the Crenshaw Coalition, Environmental Lawyers Sabrina Venskus and Noel Weiss, and a host of people who are anything BUT Republican...but know disingenuous behavior when they see it and therefore support Measure S.

And our City Council, our Mayor, and the Planning Department have been as environmentally-insensitive, as derisive of grassroots empowerment, and as much in the pockets of developers as any "let them eat cake" aristocrats we've ever seen.

So it should be remembered that those who are pro-Measure S are doing this out of a sense of volunteerism and grassroots empowerment, while those who are anti-Measure S are being PAID (Primarily Associated In Development) to fight it.

3) Finally, why are those opposing Measure S only NOW acknowledging that City Hall and Planning is out of whack, and only now acknowledging that the "Groupthink" dominating Planning has its limits?

Simply put, because they know that Angelenos of all political stripes, and who adhere to Common Sense and Fairness and Compromise, have HAD IT.

Those jackasses at the LA Times opposing Measure S, while attacking Angelenos who volunteer to support it and ignoring why their own readership is going down.

They're the same lovelies who just LOVED all the overdevelopment supported by Mayor Garcetti, even when they didn't hold up when brought to the courts.

And the Times was nowhere to be found when developer money and bizarre Planning "Groupthink" and zealotry was developing the City of Los Angeles into the toilet with respect to sustainability, livability, and economic betterment for the average Angeleno.

After all, if the City Council is NOW (with Measure S on the ballot) trying to limit developer money at City Hall, and raising the issue of addressing the decades-overdue-but-legally-mandated updating of our Community Plans and Planning Policies, why should ANYONE believe or trust the City Council, the Mayor, or the LA Times?

So rather than attacking those who are volunteering and spending their own money to save the City of Los Angeles, maybe one should look up the story of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, and respect them rather than attack their advocacy for Common Sense and Environmental Sustainability.

And rather than ignore those decrying our unsustainable Planning practices that are illegal (as upheld when they get to the courts), let's just listen to City Planners who want everything to be ... well ... legal.

1) If Measure S passes, housing and construction will go on aplenty...just not the illegal megadevelopments.

2) If Measure S passes, the focus of construction will be on affordable housing for the middle class and for Senior Affordable Housing, Student Affordable Housing, and Workforce Affordable Housing...but not so much for luxury housing unless that luxury housing is done within the confines of the law.

3) If Measure S passes, there will be plenty of apartments and opportunities to upgrade our commercial corridors to create wonderful new places for people to call "home".

4) If Measure S passes, high-density housing and development that is transit-oriented will certainly be welcomed next to train stations...but car-oriented megadevelopments will not be.

5) If Measure S passes, the opportunity for low-rise development to house the middle class can be the new focus of construction throughout the City of the Angels (even for that region south of the I-10 freeway) that prevents gentrification and empowers the middle class.

So we really do NOT need to keep lying to and confusing Angelenos. We really do NOT need to wait until the next dam breaks, with respect to any of our infrastructure needs.

Just remember: those supporting Measure S also support livability and environmental sustainability for all Angelenos.

And also remember: those supporting Measure S are those who've overseen and led us into the problems we now face with inappropriate development, and either have:

… a conflict of interest and are getting PAID, or

… just don't give a damn about the worsening lives of tired, exhausted, and increasingly-disillusioned volunteer Angelenos who just simply want to save their City.

(Kenneth S. Alpern, M.D. is a dermatologist who has served in clinics in Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside Counties. He is also a Westside Village Zone Director and Board member of the Mar Vista Community Council (MVCC), previously co-chaired its Planning and Outreach Committees, and currently is Co-Chair of its MVCC Transportation/Infrastructure Committee. He is co-chair of the CD11Transportation Advisory Committee and chairs the nonprofit Transit Coalition, and can be reached at [email protected]. He also co-chairs the grassroots Friends of the Green Line at www.fogl.us. The views expressed in this article are solely those of Dr. Alpern.)

-cw

Many people fled, and thousands entered the U.S. on tourist visas. At least 3,000 came to New Jersey, where they got factory jobs. It was the late ‘90s, companies needed low-wage workers, and nobody was asking for work permits. The refugees overstayed their visas, with few consequences. Most opted not to file for asylum, in some cases for fear of government reprisal, or for lack of the language skills perceived to be necessary to make a successful case. But also, some later told me, Indonesians were surrounded by many other undocumented workers from many other lands. It seemed to be the American norm.

Many people fled, and thousands entered the U.S. on tourist visas. At least 3,000 came to New Jersey, where they got factory jobs. It was the late ‘90s, companies needed low-wage workers, and nobody was asking for work permits. The refugees overstayed their visas, with few consequences. Most opted not to file for asylum, in some cases for fear of government reprisal, or for lack of the language skills perceived to be necessary to make a successful case. But also, some later told me, Indonesians were surrounded by many other undocumented workers from many other lands. It seemed to be the American norm.