Comments

ERIC PREVEN’S NOTEBOOK –

Paperwork is the crime--Los Angeles will spend roughly $320 million this year settling lawsuits — from police shootings to sidewalk injuries — without a single trial or moment of public scrutiny. City Hall handles it all behind closed doors. Councilmembers vote in secret, the City Attorney announces the amounts after the fact, and by the time the public hears about it, the checks are already in the mail.

It’s become routine government choreography: the city withholds case names, denies public comment, votes, and then quietly “notes and files” the outcome so it never appears on a published agenda. Technically legal, but unmistakably wrong. The process erases the very transparency that California’s Brown Act was written to guarantee.

Meanwhile, the numbers keep swelling. Rebecca Ellis of the Los Angeles Times recently reported that the County approved a $4 billion settlement to resolve claims of child abuse in foster care and juvenile halls — the largest such payout in U.S. history. Allegations of fraud and mass-filed claims by high-volume downtown law firms are already surfacing. When paperwork replaces proof, taxpayers lose twice: once to fraud and again to secrecy.

Los Angeles’ liability culture feeds on both. Downtown legal mills — some accused of paying people to sue — churn thousands of claims into quick payouts. LAPD alone burned through $107 million last quarter on excessive-force, crash, and negligence cases. These settlements never face a courtroom, only a closed-session rubber stamp from Council President Marqueece Harris-Dawson and City Attorney deputies sworn to silence. City Clerk Patrice Lattimore records the vote, files the memo, and the money vanishes from public view.

Across the street, Los Angeles County does at least one thing right: it lets taxpayers speak before the vote. Supervisors still hide behind lawyers, but they recognize that public comment is not a privilege — it’s the law. The City of L.A., by contrast, runs its litigation docket like a private corporation, shielding information until disclosure no longer matters.

Santa Monica learned what that silence costs. The city has paid more than $229 million so far to victims of former youth-program employee Eric Uller, who molested over 200 children while warnings piled up. Another 180 claims remain. One predator, one cover-up, and an entire city’s budget buckles.

The Brown Act’s spirit is simple: daylight before the gavel. Cases involving public money must be noticed, discussed, and voted on in open session whenever secrecy isn’t essential to strategy. Yet Los Angeles treats “efficiency” as an exemption. Efficiency isn’t accountability; it’s control. And control breeds waste.

City Hall’s secrecy has real fiscal consequences. Even with Mayor Karen Bass juggling union raises and layoffs, the city faces a $1.2 billion shortfall. Settlement costs are eating core services. But instead of reforming the system, officials keep feeding it — batching claims, meeting in private, calling it prudent.

There’s a better model, and it starts this week in Long Beach, where the League of California Cities is holding its annual conference for city attorneys, managers, and clerks. Smaller cities should study Los Angeles closely — and then do the opposite. Post every proposed settlement online the moment it’s announced. Provide a short summary: what happened, who’s responsible, and how much it costs. Give the public 72 hours to comment before any vote. Sunlight is cheaper than secrecy.

Los Angeles once called this kind of disclosure impossible — until I proved otherwise. In 2019 I won a Brown Act case against the city. Five years later, the culture of concealment is back. It’s time for the League’s reform-minded cities to set a new standard. Because when paperwork entombs the truth, the crime isn’t just fraud — it’s betrayal. Don’t let Los Angeles’ secrets follow you home.

(This article appeared in the Daily News on October 8, 2025.)

County Checkbook Confidential

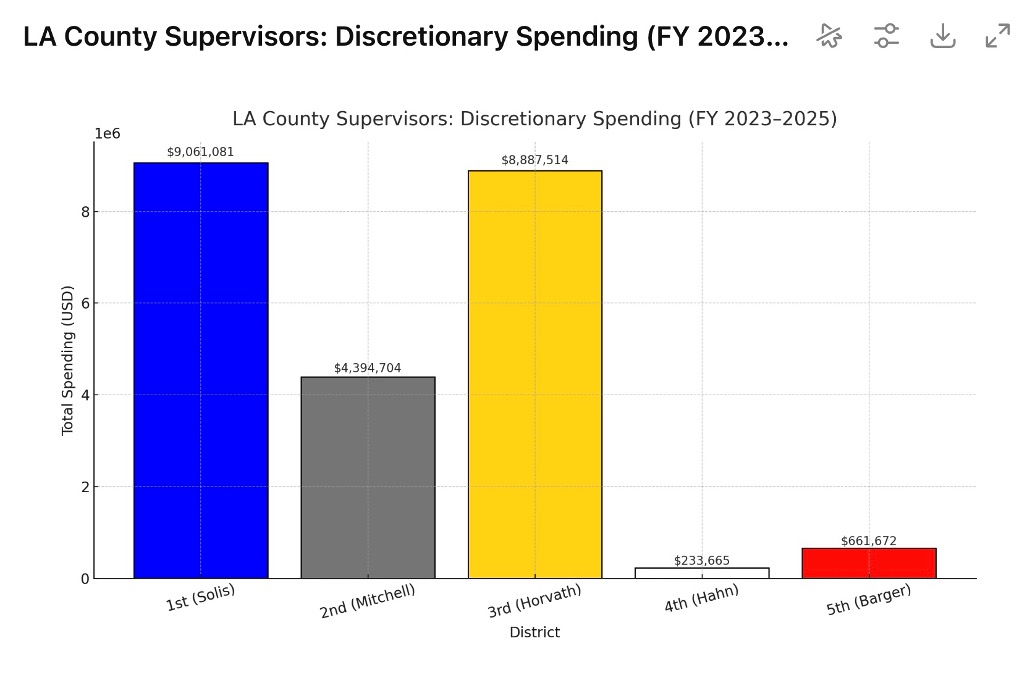

While they were baking up the largest settlement cake in history behind closed doors, in the corridor near the kitchen, the five supervisors sprayed $22,704,834 in “discretionary” money out the door — five mini-foundations with five different vibes, zero common rulebook.

Young Supervisor training.

Solis (1st) – $9,061,081. The overpowering hose. Multi-hundred-thousand grants to big social-service institutions; Downtown Women’s Center ($3M), JWCH ($851K), Plaza de la Raza ($500K). It reads like a parallel county budget.

Mitchell (2nd) – $4,394,704. The network effect. Dense clusters of $1–$50K checks across South LA and the beach cities. Same names pop up year after year — Peace Over Violence, Coro, Drew Child Development, Community Coalition, etc. Small checks, big volume, constant motion.

Horvath (3rd) – $8,887,514. The cultural endowment. Arts, equity, and civic-identity spending: Project Angel Food, Equality California, Holocaust Museum LA, Center Theatre Group, CicLAvia, Drag Arts Lab — a curated portfolio of causes that photograph well.

Hahn (4th) – $233,665. The minimalist. Civic clubs, school foundations, small museums; rarely above five figures. Either prudence or disengagement — but unmistakably modest.

Barger (5th) – $661,672. The Chamber-of-Commerce style. Rotary breakfasts, chambers, veterans groups, service clubs, YMCAs. Lots of $500–$2,000 checks, steady suburban goodwill.

Bottom line: $22.7M out the door, no published scoring rubric, no countywide criteria, no outcomes reporting. Five different philosophies; one common feature — discretion.

Un Poquito Mas detail:

First District

The First District spent heavily, repeatedly topping the charts with multimillion-dollar discretionary outlays.

For FY 2024–2025, the total exceeded $8.9 million, anchored by large institutional grants. The biggest checks went to the Downtown Women’s Center ($3,000,000) and JWCH Institute ($851,000), with additional six-figure awards to Neighborhood Legal Services ($500,000), East Los Angeles Women’s Center ($250,000), CHIRLA ($300,000), Plaza de la Raza ($500,000), and CARECEN ($250,000).

This district’s pattern leans toward homelessness, immigrant advocacy, and women’s services—but the sums are staggering. Even small local governments and school districts, like City of Baldwin Park ($322,551) and Hacienda La Puente Unified School District ($50,000), appeared on the roster.

By FY 2025 Q1, the First District had issued one notable payment: $100,000 to the El Monte Business Alliance, signaling continued use of discretionary funds for business-oriented or community development groups.

Second District

The Second District’s discretionary spending is broad, fragmented, and often focused on community programs, youth, and wellness nonprofits. Across FY 2025 Q1, it disbursed about $620,590, spread across more than 60 separate organizations.

Typical recipients include East Side Riders Bike Club (two separate grants totaling $23,500), Dolores Huerta Foundation, St. Joseph’s Center, and smaller but recurring beneficiaries like Open Arms Food Pantry, Brown Bag Lady, A Sense of Home, and Urban Voices Project.

The district’s giving style mirrors its grassroots focus—short bursts of $5,000–$10,000 allocations to small, localized programs, often with cultural or social equity missions. Names like Film Independent, LA Promise Fund, Rediscover Center, and Essential Access Health appear, pointing to a deliberate mix of creative and wellness initiatives.

Third District

The Third District’s discretionary accounts read like a philanthropic festival—hundreds of mid-sized gifts and recurring favorites from year to year.

For FY 2023–2024, the district spent about $2.05 million, with signature awards to Project Angel Food ($500,000), Los Angeles Opera ($650,000), and a cluster of arts and advocacy groups: Equality California, City of West Hollywood, Peace Over Violence, Venice Pride, CARECEN, and The Wall Las Memorias Project.

By FY 2024–2025, the outlay ballooned even higher, surpassing $5.4 million, marking the Third as one of the County’s most liberal spenders. The recipient list exploded—over 200 line items ranging from Southwest Voter Registration Education Project ($250,000) and Asian Pacific American Leadership Foundation ($50,000) to a sea of $5,000–$25,000 arts, equity, and emergency grants.

Notably, repeat beneficiaries included Somos Familia Valle, DIY Girls, Happy Trails for Kids, Coro Southern California, Homeboy Industries, and Friends of Westwood Recreation Complex.

In Q1 2025, the Third District kept pace—roughly $1.4 million went out the door, highlighted by Project Angel Food ($500,000), Santa Monica Arts Foundation ($95,000), Holocaust Museum LA ($100,000), City of West Hollywood ($75,000), and an expanding lineup of civic and identity-focused organizations from Equality California Institute ($35,000) to Black Lives Matter Grassroots ($10,000).

Fourth District

The Fourth District’s giving patterns are smaller but still eclectic.

In FY 2023–2024, total discretionary grants reached $50,000, with typical recipients being small, service-oriented nonprofits like Kiwanis Club of Long Beach Foundation, Food Finders, Shelter’s Right Hand, and New Horizons Caregivers Group.

For FY 2024–2025, the total grew to about $107,900, still modest by comparison but spread across dozens of tiny organizations—Food Forward, South Asian Network, Freedom 4 U, Friends of the Cerritos Public Library, and South Bay Lesbian and Gay Community Organization among them. This is a district of micro-grants—mostly in the $1,000–$5,000 range—aimed at local schools, libraries, cultural groups, and neighborhood charities.

By Q1 2025, the district had issued a mere $4,800, all to Holy Family Catholic Church ($2,500) and South Bay Center for Counseling ($2,300)—a nearly symbolic output compared to the first and third districts’ massive distributions.

Fifth District

Traditionally the most fiscally restrained, the Fifth District still manages a long roster of hyper-local recipients.

For FY 2024–2025, spending totaled roughly $208,535, and the pattern is telling: an array of chambers of commerce, Kiwanis and Rotary clubs, school foundations, churches, veterans groups, and historical societies. Nearly every check is under $2,000, with very few exceeding $3,000.

By Q1 2025, the Fifth District distributed another $40,300, largely to the same civic and small-business ecosystem—YMCA of Glendale, Coro Southern California, Food Forward, Maryvale, Antelope Valley College Foundation, and several Kiwanis and Rotary foundations.

This is retail politics at its most literal: small, steady checks to community players across Pasadena, Glendale, Santa Clarita, and the Antelope Valley.

The Los Angeles Politics Class from Occidental went to City Hall while County hall paid out...

Largest Single Grants (2022–2025)

| Organization | Amount | District |

|---|---|---|

| Downtown Women’s Center | $3,000,000 | 1st |

| Special Services for Groups, Inc. | $1,000,000 | 3rd |

| 18th Street Arts Center | $889,000 | 3rd |

| JWCH Institute | $851,000 | 1st |

| Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum | $700,000 | 3rd |

| Los Angeles Opera | $650,000 | 3rd |

| Peace Over Violence | $600,000 | 2nd |

| Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles County | $500,000 | 1st |

| Plaza de la Raza | $500,000 | 1st |

| Project Angel Food | $500,000 | 3rd |

| Community Coalition | $500,000 | 3rd |

| LA Family Housing | $500,000 | 3rd |

| TreePeople Land Trust | $500,000 | 3rd |

| St. Joseph’s Center | $500,000 | 3rd |

| Venice Community Housing Corporation | $500,000 | 3rd |

| Los Angeles Philharmonic Association | $350,000 | 3rd |

| City of Baldwin Park | $322,551 | 1st |

| CHIRLA | $300,000 | 1st |

| The Wall Las Memorias Project | $300,000 | 1st |

| Pacific Coast Regional Small Business Development Corp. | $298,000 | 3rd |

| CARECEN | $250,000 | 1st |

| East Los Angeles Women’s Center | $250,000 | 1st |

| Southwest Voter Registration Education Project | $250,000 | 3rd |

| Center for Asian Americans United for Self-Empowerment | $250,000 | 3rd |

| APLA Health & Wellness | $250,000 | 3rd |

| UCLA LGBTQ Campus Resource Center | $250,000 | 3rd |

It’s a telling cross-section: First District’s heavy investment in health and social service nonprofits; the Second’s standout with Peace Over Violence; and the Third’s lavish, arts-and-advocacy sweep that seems to treat six figures as small change.

Source: Discretionary & Community Programs expenditure logs (FY 2023–2025).

Snapshot on Besties:

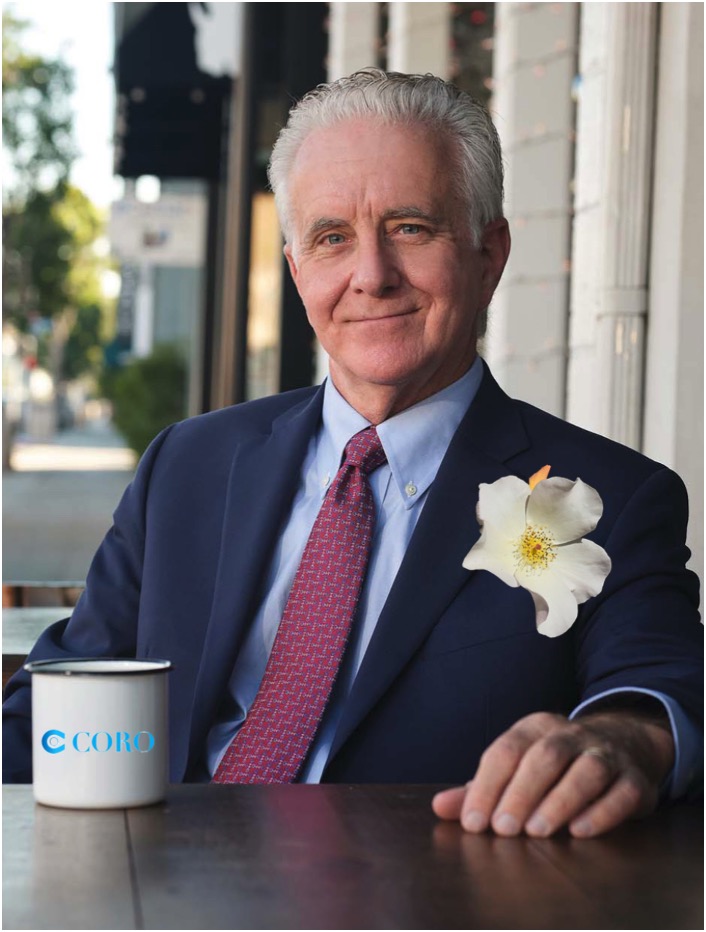

Coro Southern California

Not a fellow himself but Adrin Nazarian was and Areen Ibranossian serves on the board of directors

A countywide favorite of the political class, Coro is sprinkled through nearly every year’s ledger like parsley. Across four districts (mostly the 2nd), the civic leadership nonprofit has collected roughly $67,000 since 2022. It’s the supervisors’ idea of an heirloom investment — cultivating “emerging leaders,” many of whom end up in City Hall hallways. Coro is what you fund when you want to look serious, bipartisan, and vaguely educational.

YMCA / YWCA

The Y’s brand power is eternal. Together, the YMCA and YWCA have drawn over $350,000 across every district and fiscal period in the sample. Crenshaw, Glendale, San Gabriel, Santa Anita — everyone gets a little cardio with their cash. The Y is political yoga: flexible, wholesome, and photogenic. A check to the Y is a handshake to the community that no one can criticize.

Traci Park of CD11 and Lindsey P. Horvath of SD3, who put her name on the check!

Peace Over Violence

The crown perennial. Between the 1st, 2nd and third Districts alone, Peace Over Violence has received about $728,500, a staggering total for one organization run by Patti Giggans who scrapped with former Alex Villanueva Sheriff for Sheila Kuehl. It’s the kind of line item that makes staffers smile: unimpeachable name, guaranteed applause. But beneath the branding, it’s a reminder that “discretionary” means concentrated — vast sums can flow to a chosen few while the rest of the nonprofit garden withers.

(Eric Preven is a Studio City-based television writer-producer, award-winning journalist, and longtime community activist. He is known for his sharp commentary on transparency and accountability in local government. Eric successfully brought and won two landmark open government cases in California, reinforcing the public’s right to know. A regular contributor to CityWatch, he combines investigative insight with grassroots advocacy to shine a light on civic issues across Los Angeles.)