CommentsCONSIDER THIS--Recently, I’ve been catching up on episodes of “The Americans.” It’s a television program about Russian sleeper agents posing as a middle-class couple in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. in the Reagan era. In one show, a veteran KGB agent talks about a colleague who was declared an “enemy of the people” and taken away never to be heard from again.

Donald Trump’s recent tweet referring to media as an enemy of the people suggests he may have picked up the phrase from his pal ex-KGB agent Vladimir Putin. Though the rhetoric might be borrowed from Soviet-era Russia, presidential enmity toward the press has a long history in America.

The first official action aimed at media was the Sedition Act of 1798. President John Adams and the Federalists were so put out by their opponents’ newspapers they passed a law making it a crime to “defame” the government. Punishment included fines and imprisonment. Although clearly unconstitutional, it would be five years before the Supreme Court established its right to review and rule on the actions of Congress. In any event, the law expired in 1801, at which time those in jail were released and those who had been fined got their money back.

Jefferson and his successors understood freedom of the press was necessary to making democracy work. That didn’t mean they liked it. But they understood there was only one First Amendment and it protected them and their supporters the same as the opposition.

It’s only in the last 80 years or so that technology has allowed presidents direct access to the American people. Franklin Roosevelt used the power of radio to reach out in a series of speeches called “fireside chats” to promote his programs and positions on events at home and abroad.

Truman was often vilified by the press and once threatened to beat up a columnist who criticized his daughter, Margaret, who had embarked on a career as a professional classical singer.

As president, Lyndon Johnson installed three televisions in the oval office so he could watch the major network news programs at the same time. If he didn’t like what he saw, he’d call network executives and complain about the coverage.

Johnson understood the power of media (he owned radio and TV stations) and especially the credibility of news broadcasters like Walter Cronkite of CBS, often referred to as the most trusted man in America. When Cronkite criticized the war in Vietnam, Johnson said, “When I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.”

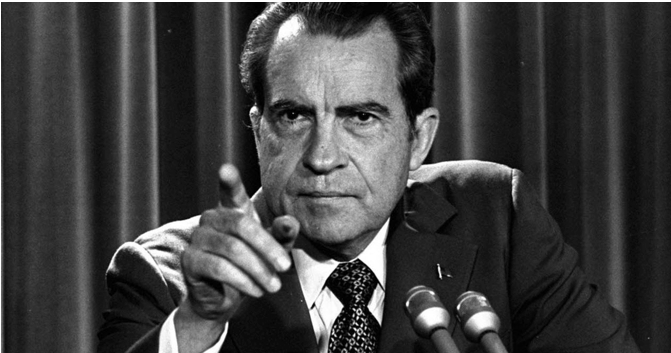

Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, hated the media. Questions about Nixon’s relationship with campaign donors and acceptance of gifts started as early as the 1952 campaign, when Nixon was running for vice president. Ten years later, after losing the California governor’s race, Nixon famously told reporters, “You’re not going to have Nixon to kick around anymore.”

In 1969, comeback achieved, Nixon took the oath of office and sent his vice president, Spiro Agnew, out to declare war on the media. Calling them “nattering nabobs of negativism”, Agnew chastised TV networks and major market newspapers as out of touch with the average American. Nixon claimed to represent the “silent majority”, who didn’t like hippies, supported law and order, and were fine with whatever the government wanted.

Mark Twain warned about picking fights with people who bought ink by the barrel. Instead of intimidating the press, Nixon invigorated them. The first major fight happened when the New York Times and Washington Post published secret Department of Defense documents critical of American actions in Vietnam. When the government tried to stop publication of “The Pentagon Papers”, the courts turned it down saying it could not engage in prior restraint.

Along the way to Watergate, reporters wrote about systemic corruption involving shadowy figures engaging in bribery and dirty tricks. Syndicated columnist Jack Anderson was a particular thorn in the side of the Nixon administration. Ultimately, the burglary at the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic National Committee was the thing that broke open the Pandora’s box of wrongdoing by Nixon and much of his government. What ended it was Congressional committees, grand juries, independent prosecutors, and judges who brought the full weight of the law to bear on conspirators, high and low, who believed the ends justified the means.

If there is a key to predicting the future of the Trump administration, this is it. Trump can refer to the press as an enemy of the people. He can deride the judiciary and claim to be above the law. He has the advantage that half of Americans have tuned out truth and embraced “alternative facts”. But he does not have enough to become a dictator. At least not as long as the First Amendment still guarantees freedom of speech.

(Doug Epperhart is a publisher, a long-time neighborhood council activist and former Board of Neighborhood Commissioners commissioner. He is a contributor to CityWatch and can be reached at: [email protected]) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

05

Thu, Mar