Comments

SUPPORT SERVICES - One of Housing First’s keys to success is the provision of wraparound services. Once a person is in stable housing, he or she benefits from needed support services, such as mental health, substance abuse recovery, and job counseling. Because that person has a home, those services can be provided more efficiently and effectively than they could on the street or in a congregant shelter. Several empirical studies support this model, concluding people in permanent supportive housing are healthier, happier, and more likely to stay housed than those in other shelter situations. In her campaign literature, Mayor Bass said robust mental and substance abuse services are vital to getting people off the streets and back into mainstream society.

The problem is, in Los Angeles, the support services needed to make Housing First successful are virtually non-existent. As with most of the failures of homelessness intervention programs, the reason why L.A. can’t connect people with the services they need is a combination of organizational problems, bad policy, and resistance to change.

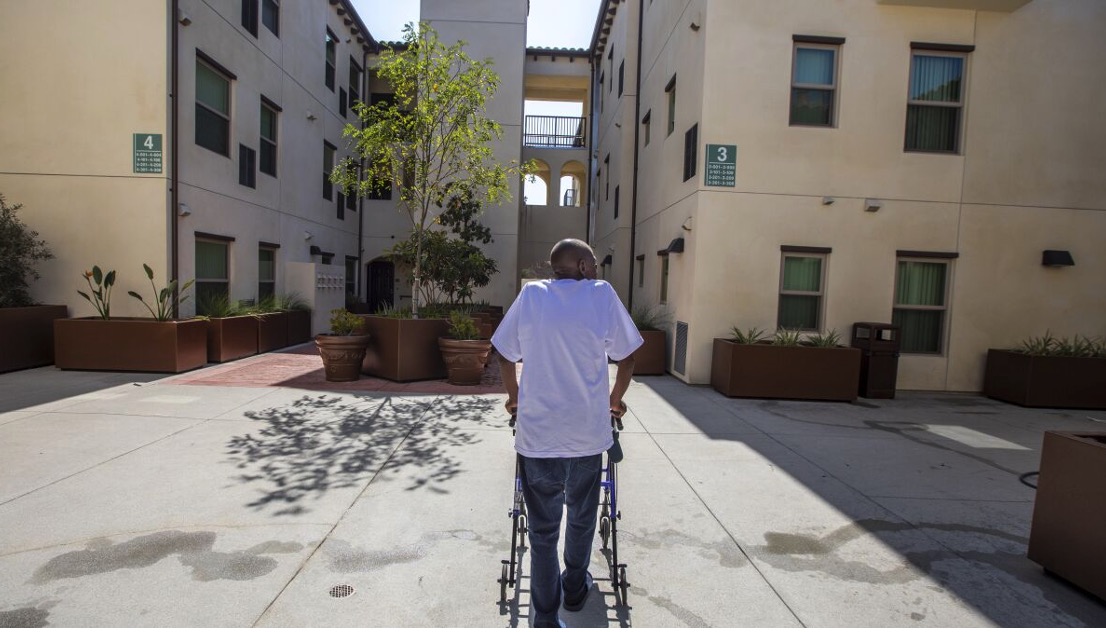

The dearth of support services is probably the worst-kept secret in L.A. County. Supervisor Lindsay Horvath, in a May 22 speech at Belmont Senior Care, discussed the lack of coordination and accountability endemic to LAHSA’s structure. LAHSA has more than 1,000 contracts with about 100 service providers. As Horvath stated, such a complex network of contracts and organizations leads to decreasing levels of accountability. In a March 2023 report, McKinsey & Co, a public/private think tank, noted the City of New York has only about 517 contracts, and does a much better job sheltering the unhoused. In an October 2022 All Aspects.com report, Christopher Legras poignantly describes the effect of the system’s inability to provide needed services to people in supportive housing. The article’s subject, Bryan, needed constant care and supervision, especially to ensure he was taking the medication to manage his schizophrenia. Instead, he received a couple of desultory visits and was soon back out on the street, current whereabouts unknown. In Supervisor Horvath’s words, such as a system is an embarrassment.

Without wraparound services, Housing First collapses, descending to nothing more than a transitory stop in an endless cycle of streets to shelter to housing and back to the streets. Because LAHSA does such a poor job tracking its outcomes, nobody really knows how many people who are counted as “housed” wind up back on the streets, but anecdotal evidence suggests that number is substantial—McKinsey pegs it at 16 per day. As we know, one of the reasons for the Skid Row Housing Trust’s financial collapse was the exorbitant costs of repairs from damage caused by tenants suffering some type of mental break.

How, with an $800 million budget and contracts with 1,000 service providers, does LAHSA fail to deliver necessary support services to the unhoused? The biggest problem seems to be complexity. Services are fragmented, with one provider handing off specific services to others with little overarching coordination. As the McKinsey report stated, “ LA has no county department exclusively responsible for homelessness, with responsibilities and decision making dispersed across various agencies, the county, and individual cities.”

To better understand how such fragmentation could exist, I asked LAHSA to send me a sample service provider contract for a transitional living center. I received a $191,000 contract between LAHSA and Safe Place for Youth (SPY), for support services at a shelter in Venice.

The document is an impressive 320 pages long. Unfortunately, little of its heft is devoted to describing the required services and performance. The contract included SPY’s 37-page employee manual, (11.5% of the total pages), which has nothing to do with its service requirements. Much of the rest is boilerplate. There is a 14-page Scope of Work (SOW), but it is process-centered rather than focused on outcomes. In Section 10, SPY is required to provide the following services:

10.1 Twenty-four (24) hour bed availability

10.2 Intake and Assessment

10.3 Case Management

10.4 Residential Supervision

10.5 Crisis Intervention & Conflict Resolution

10.6 Provision of Meals

10.7 Provision Restrooms & Showers

10.8 Safety and Security Protocols

The remainder of the SOW describes processes SPY is to follow when reporting its activities. The processes are supposed to produce and implement a Housing and Services Plan for each client, which in turn is supposed to get program participants into stable housing as quickly as possible. Participants must sign the plan, suggesting they agree to its provisions.

What is missing from the SOW is the actual, direct provision of support services. SPY is required to “refer” participants to mental health or substance abuse services, but it doesn’t provide those services itself. So “Crisis Intervention” is really nothing more than referring a youth in crisis to another organization. SPY’s job stops with the referral.

Page 238 of the document contains three “performance indicators”:

Nightly Bed Utilization: 95%

Exits to Permanent Housing: 50%

Minimum Number of People to be Served: 15

None of these are true performance measures. Filling 95 percent of available beds is a workload factor and says nothing about quality of services or shelter. Having 50 percent of clients exit to permanent housing sounds like a performance measure, except SPY has no responsibility or control over what happens to those clients once they’re in the housing (refer to the McKinsey report and All-Aspects article cited earlier). At $191,00 and a minimum number of 15 people to be served, SPY charges $12,730 per person to provide shelter, food, and service referrals to their clients.

One may assume actual support services like mental health counseling and substance abuse recovery are handled by third parties, perhaps the County’s Mental Health Department, or another layer of contracted providers. Now we see the weakness in the system. Let’s assume the County is responsible for providing mental health services to clients referred by SPY. According to Supervisor Horvath, the Mental Health Department is chronically understaffed; it takes a year to hire mental health professionals. Several months ago, the Mental Health Director told the L.A. Times he would have to hire thousands of providers to meet the needs of 69,000 unsheltered homeless. (This assumes LAHSA continues to follow the same inefficient models it now uses). There simply aren’t enough professionals to properly serve all those in need.

Even if there were enough staff to provide the needed services, there is no guarantee those who need them would use them. SPY’s contract specifically states all services are to be provided on a No Barrier/Housing First basis. People entering the shelter do not have to commit to enter or participate in any kind of recovery program. No Barrier-Housing First is based on the theory that people with behavioral problems should not be prohibited from entering the housing system; they are more likely to accept services once they are housed. Therefore, people with no commitment to sobriety are given housing units, which are already in precariously short supply, and little chance of getting those services even if they do want them. This is a recipe for disaster, as described by the Rev. Andy Bales, the outgoing Director of the Union Rescue Mission. URC requires a commitment of responsible behavior from participants to be allowed to continue to receive services. In other words, it treats participants as equal partners instead of passive victims. URC has an impressive record getting people out of the homelessness loop.

No Barrier-Housing First advocates insist imposing behavioral requirements on participants is counter-productive because many people are unwilling or unable to enter shelters that require sobriety commitments. Advocates say once people are in shelter or housing, they are more likely to accept and benefit from support services. While this is a nice theory, in reality it is a complete failure, as documented in this New York Post article. The vast tent encampments surrounding many transitional shelters are sad testaments that people with no commitments tend to treat shelters as temporary resources, going inside for meals or showers, then returning to their tents where they can live the lifestyles of their choice. Exacerbating the situation, the City has created “amnesty boxes” at some transitional shelters, where clients can place weapons and drug paraphernalia, eat a meal and take a shower, and then pick up their “property” on the way out. Allowing this kind of in-and-out traffic makes acceptance of any support services highly unlikely, and results in higher crime rates that have been documented in areas surrounding shelters. That, in turn stiffens community resistance to establishing new shelters.

The combination of LASHA’s poor contract management, the city’s counter-productive shelter policies, and structural problems such as staffing shortages, has created a perfect storm that denies unhoused people the services and support they so desperately need. LAHSA’s contract is a perfect example of putting process over goals. The contract is all about following the proper procedures, under the assumption that those procedures will result in the desired outcomes. When those outcomes fail to materialize, there is no provision for implementing alternatives. We see the results in the revolving doors in local shelters, in the absurdly high costs of managing supportive housing facilities, and in the human suffering we allow to continue unabated on our streets.

As Supervisor Horvath said, LAHSA needs to get back to its core mission of coordinating services among providers. She advocates for governance reform of the agency, so its performance can be measured, and its changes made as needed. She is one of the few elected officials who sees the realities of the system’s current failures. She needs more support from her fellow officials and from the public.

(Tim Campbell is a resident of Westchester who spent a career in the public service and managed a municipal performance audit program. He focuses on outcomes instead of process.)