Comments

LA’S UNHOUSED & MENTAL HEALTH - When I was a full-time public sector performance auditor, I often encountered situations where managers convinced themselves their programs would work if only they had a little more time, or a little more money, or if the organization properly supported them. They would often cite the success of similar programs in other cities, or studies that showed they were doing everything right, and some external condition is causing a program to fail. I found that introspection, the ability to admit something wasn’t working because it was poorly executed, was a rare virtue.

We see the same thing play out in almost every homeless intervention program in California, and especially in Los Angeles. Advocacy groups and government agencies doggedly insist No Barrier/Housing First is the best (and only) remedy to the crisis. They cite scholarly studies as proof, and use experiences in other regions, along with the occasional anecdotal personal story, to tout Housing First’s successes. One of the latest success stories making the rounds on the Internet is a YouTube video about the successful Housing First policies of Finland. Finland is an odd choice since its population is about half that of L.A. County and its government structure is completely different than the United States’.

Citing the results of studies and success stories from other jurisdictions can be problematic. First, many of these studies were sponsored by homeless agencies, so they tend to show the results the agencies want. Second, although academic studies can be compelling because they are unbiased, they are often based on theories of what people will do under a given set of circumstances, and use narrow population sampling. For example, a rational person living in a tent would readily accept a housing offer, assuming the housing was safe, clean and provided a sense of privacy. Since housing provides stability, a housed person is more likely to benefit from support services like substance abuse recovery or job counseling. In many cases, this is true, if those services are actually provided.

Based on my review, there are two fundamental flaws with most “impartial” studies. First, they assume people will make rational decisions in a given situation, and second, they tend to study locations where Housing First is part of a comprehensive package of shelter and services; such is not the case in Los Angeles.

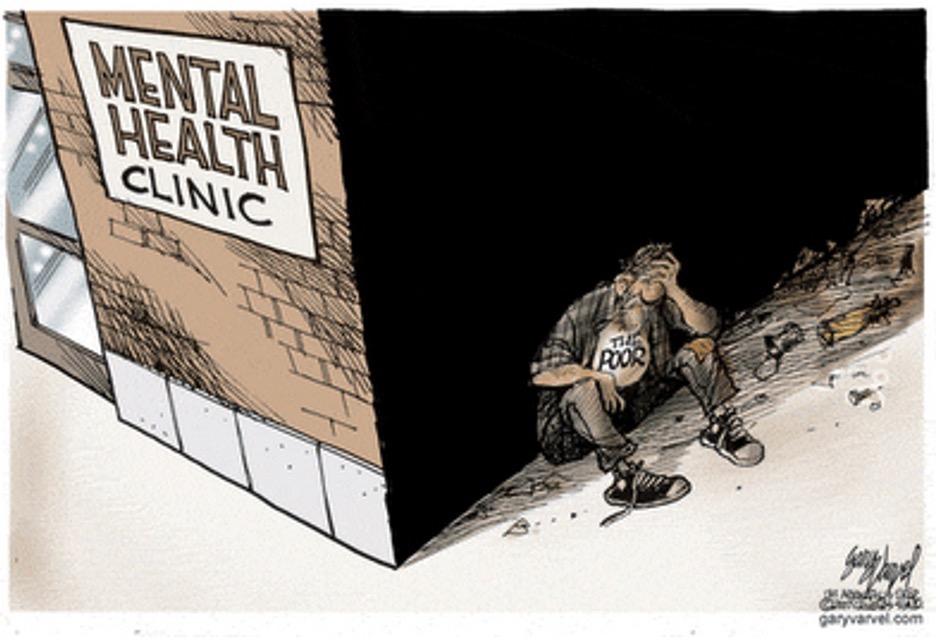

When it comes to making rational decisions in one’s own interest, we must remember 50 to 75 percent of L.A.’s unhoused have serious mental health and/or substance abuse problems. By their nature, people in these situations are unable or unwilling to make rational decisions. Offering housing to a delusional person who thinks a tent is his home is a waste of time. Assuming someone with a serious addiction problem will voluntarily join a recovery program just because she is offered housing is naïve at best. A No Barrier/Housing First policy is merely an offer of a different kind of shelter for as long as recipient chooses to accept it, and the provider can tolerate the costs and tenant’s behavior. Skid Row Housing Trust’s financial collapse should be a warning to other agencies that think the current model can be successful.

Housing First can be successful if it is one component of a toolbox of intervention strategies, including transitional housing and support services. (USICH 2020 Report). Unfortunately, in Los Angeles, Housing First has morphed into Housing Alone, where a near-obsessive emphasis on construction has financially starved other programs, and support services are virtually nonexistent.

Two separate studies show Housing Alone does not work. One, by the Stanford University Economic Policy Institute, stated “Meanwhile, Housing First showed no effects in reducing drug use, alcohol consumption, psychiatric symptoms, or enhancing the quality of life”. The other study, by the National Interagency Council on Homelessness, stated Housing First used as a standalone program is ineffective at reducing homelessness or behavioral and substance abuse issues.

I am not belittling the work of serious statistical scientists and survey professionals. Rather, I am criticizing the misuse some agencies make of their results. The difference between what should be and what is an important concept in professional auditing. Much of our work consists of documenting criteria (what should be) versus actual results (condition). The auditor’s job is to find out what’s causing the difference and recommend corrections. The program managers’ job is to implement changes to produce the desired outcomes.

Nevertheless, California’s public agencies, from the state to most cities, insist Housing First (Housing Alone) will work, even as the outcomes—the number of unhoused people—continue to worsen. They fixate on the criteria and ignore the condition. They are what I refer to as “theoretical managers”; ones who read all the manuals and books on how things should work, but are incapable of change when the theories don’t work. This syndrome isn’t unique to homelessness; I am sure we all have experience dealing with executives who refuse to admit when their programs aren’t working. In the case of homeless interventions, the consequences have been increasing homelessness, both in terms of numbers and the proportion of those who have serious behavioral problems.

The real-world consequences of allowing theoretical leaders to determine housing policy are all around us, living in squalid camps and decrepit RV’s, while the promised housing construction proceeds at a glacial place. Despite experts who claim that No Barrier Housing First is the best way to get people into stable shelter and recovery, real-world homeless services providers like the Rev. Any Bales of Union Rescue Mission beg to differ. His recent editorial in The Daily Post lays bare the empty promises and devastating consequences of L.A.’s misguided policies.

In my experience, when an organization’s leaders refuse to admit their programs have failed, they become defensive and try to deflect blame to external factors. (And by the way, an auditor’s job isn’t to place blame. Its to assign accountability). In the case of homeless agencies, they use an arsenal of excuses, including:

- The complexity argument. There’s been no progress because homelessness is more complex than most people realize. There are myriad causes of homelessness, from job loss to substance abuse. This is an odd argument to use when one insists there is only one universal remedy (Housing First) to a crisis with multiple causes.

- Uncontrollable external causes. This is where we find the “homelessness is caused by a housing shortage” and economic disparity arguments. The agencies insistence that homelessness is caused by a housing shortage, despite a dearth of empirical causative data, justifies their fixation with new construction at the expense of other more economical and effective programs. Blaming amorphous concepts like economic injustice absolves the agencies of any responsibility for failed outcomes.

- Blaming society and name calling. When all else fails, advocates and the agencies that encourage them trot out cliches like NIMBY, “hating the homeless” or “criminalizing poverty.” The well-earned dismal reputation providers have for mismanaging shelters is really just community opposition. Expecting housing to be built with the community’s expectations and desires in mind is just NIMBY-ism. Calling attention to the real-life consequences of allowing camps to proliferate criminalizes poverty.

(Tim Campbell is a resident of Westchester who spent a career in the public service and managed a municipal performance audit program. He focuses on outcomes instead of process. Tim is a regular contributor to CityWatchLA.)

Absent proactive and dynamic leadership, organizations don’t change unless they’re made to. Given the small interlocking world inhabited by homeless agency elites like Va Lecia Adams Kellum, LAHSA’s CEO and former head of St. Joseph’s Center, and Ashley Bennet, Kenneth Mejia’s new “Director of Homeless Program Accountability”, and founding member of advocacy group Ground Game LA, there is little chance change will come from within. Change must come from external forces, either by voters who support reform candidates, or by a disastrous collapse of the entire failed homeless response structure. Unfortunately, until change comes, hundreds of millions of dollars will be wasted and thousands of people will die on the city’s streets.