Comments

GELFAND’S WORLD - Among all the political infighting and earthquake tragedies of the past week, we had a little ray of culture and entertainment here in the south bay. It provided a chance to think about the state of our video and entertainment industries (the use of the plural is intentional) and the overall development of our culture over the past century.

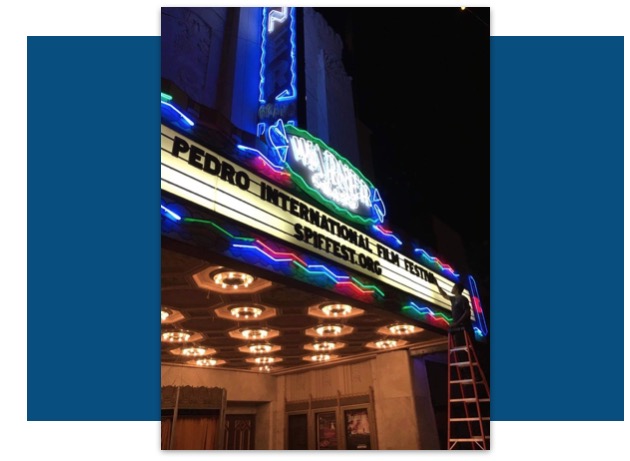

That little ray of culture was the San Pedro International Film Festival, or SPIFF for short. I must start by giving my one little disclosure: I have been involved with the festival and a member of its board of directors for the time that it has been in existence, which has now reached 11 years. I don't get a cent for doing what I do, but I get the chance to do volunteer work.

The SPIFF may be best known for its yearly screening of the Oscar nominated short films (Feb 25; Mar 4 and 11) as described here, but last weekend we had the staple of many film festivals, the short films that are entered by lots of unknown filmmakers, people trying to get a foothold in the industry, and newbies just in it for love.

So, what is a short film, exactly? I don't think there is an exact dictionary definition worth repeating, but the ones that get shown in festivals have the following characteristics:

They are, in general, maybe 5 minutes to 20 minutes in length. In this sense, they resemble the movies that were shown in storefront theatersback at the dawn of the film industry. These became known as "one reelers" based on their use of one reel of 35-millimeter film. More on this a little later, when we talk about the movement from film to digital projection, and how it affects and will affect the whole future of 21st century culture.

The next thing about these films is who makes them and they're surprisingly high quality. But in order to take this up, we first have to say just a little about the film festival circuit. Everybody's heard of the Cannes Film Festival or about Sundance. These are major events where first run feature-length films are tried out in advance. Winning an award at Cannes or Sundance is good for publicity and increased ticket sales.

This is exactly what our little short-film festivals are not. In the smaller festivals, the filmmaker pays an application fee (average around $30) with the hope that his/her film will be accepted and shown to a live audience.

But the films we see at SPIFF and other such festivals will not be shown for money at commercial theaters. They are made for love, and for practice, and as a way to get your work seen by the people who can hire you or will invest in your feature length film in the hope of making a lot of money. People with an investment eye will be looking at short films to see if they are competently made in terms of camera work, lighting, and sound quality, and if the filmmaker knows how to tell a story. Major mistakes will be noticed, as will the rare bit of talent that manages to find its way through.

At the level of SPIFF and other festivals, the short films are of high quality. They have clear pictures -- as good as what you see on your modern wide screen television or in a multiplex theater. The sound quality is generally excellent. In every sense, the image is as good or better than what you might see if you were to visit one of the theaters that shows reruns of films taken from the older film libraries at Sony or Warner. In fact, the image quality is often better, because old films are usually characterized by the presence of scratches and dust spots and the fading of the color over the course of the years. With video, it's pretty much there or not there, rather than being partially present as a scratched image playing across the screen.

And this improvement in image quality is a symptom of a change that the whole industry is going through, the migration from film to video format. This has a major effect on lowering costs, since the video format does not require the presence of silver to form the image.

So let me tell you about one talented filmmaker whose work was shown at SPIFF-2023, and who I got to talk with at some length on Sunday.

Kevin James Hogan brought a film called Secret Honor. It opens with two guys -- one white and one black -- in an old car, driving somewhere in the Los Angeles neighborhood east of City Hall. The black guy is reciting some sermon he heard at church (with great ardor), and the white guy (in beard and shades, no less) is being as cynical as if he were a cop. They both know street lingo, including one point where one calls the other "Dog," a term of endearment on the L.A. streets going back a couple of generations.

The chatter continues, and I have to say that we, the audience, aren't exactly clear on what it is all about. But we are becoming interested. That is a real plus -- this ability to create dramatic tension and mystery in the opening moments, with the implied promise that, at some point, we will learn who is about what.

Here's the summation of the film: The black guy (Demarcus) is played by Turen Robinson. He has the white guy (Victor), played by Ben Brown, along for help in a meeting he is about to have with a bookie who is into him (Demarcus) for three thousand dollars. Victor understands that the bookie is a bad guy who will do serious harm to Demarcus absent some success at the imminent negotiations. Demarcus, meanwhile, is babbling in a not-very-effective attempt at denial. They meet the bad guy bookie, and the conflict is settled by Victor taking on the bad guy in a momentous fight which results in the bookie on the ground, unconscious.

One additional little plus. The bad guy has brought along his enforcer, a huge man of obvious strength and skill in committing battery. Victor refers to him not by some old cliche like Refrigerator, but by the nickname "Beer Truck." It's little nuances like this that cause one short film to stand out from the others.

And Oh Yes, this man of violence is not just about violence for its own sake. He has his own code of honor, and we learn about it as he explains why he didn't actually kill the bad guy with his bare hands, even though he could have. I seem to have seen that same tough guy with a code of honor going back to Richard Boone in Have Gun Will Travel, or Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo and half a dozen other tough guy flicks, or James Arness as Marshall Dillon. You can fill in your own blanks for other such roles, because it is a classic story with a classic character. (Lady MacBeth and King Oedipus come to mind as characters with a flair for violence who suffer the pangs of conscience.)

But notice that this iconic character is hard to create, and is easy to lose, either at the level of the actor, or the director, or even the cameraman.

I noticed two things that made Secret Honor different from most of the other films. The first is that the filmmaker (as he told me in our conversation) starts from the standpoint of a writer rather than a photographer. It was obvious from the script language and the plot arc that considerable thought had gone into the storyline. The other thing was the look and demeanor of the tough guy with a heart of gold (aka Victor). At first, we wondered if he was an undercover cop, based on his low-emotion approach to Demarcus' problem. It turns out that Ben Brown is a professional actor who is currently playing a police officer on East New York. I sense that he was playing the role of Victor more or less as an undercover cop, even though the story did not ultimately take him there.

So the storyline involves a tough guy who only fights tough, but otherwise acts reasonable, and manages to sell the character to the audience by coming from a cop-like demeanor. It's an interesting approach, and suggests that there may be a future for this collaboration between writer/director Kevin James Hogan and actor Ben Brown.

There were a few other short films that appealed to me at this SPIFF.

Gypsy Rose Leezinski is the story of a nerdy fellow who can't get a girl and seeks the help of a fortune teller by the above name. (She's a Gypsy fortune teller by the name of Rose Leesinski, hence the title -- get it?) The film begins by making fun of the pretensions of fortune telling, including a Gypsy who is sarcastic about life and the client in front of her. But there is hope. She directs him to a location that turns out to be Warehouse 1 at the Port of Los Angeles (out my window to the left, literally, and site of the original Laurel and Hardy comedy called Putting Pants on Philip). Our nerd is supposed to be looking for a woman who will be wearing red. He goes there, and up pulls a police car with a black woman in a black uniform, and it starts badly. But she lets him off with a warning and he releases a little of his anxiety with a joke, and she responds by -- ever so seriously -- complaining that somebody stole every toilet in the police station, and although there are leads, right now the police have nothing to go on. . . And eventually he gets the joke and smiles, and she say, "I got you there, didn't I?" and it is love. And the camera follows down to her name tag, which says "Redd."

So filmmaker/director Lucia Sherman has made one of the two or three best shaggy dog stories ever. At least in short film. And one more thing. The ending of the film involves the camera pulling away from the characters and the sound going more distant, and we hear a bit of romantic banter along the lines of "Do you like bike riding?" It's true love, and the director has managed to convey the essence of Meet Cute and a peon to the pun all in a matter of moments.

The Tale of Captain Fortyhands is a pirate story with strong production values and beach shots taken right at what's now called Royal Palms, used to be called White's Point, and was used in film going back to D.W. Griffith and Mary Pickford. In other words, another San Pedro pirate film. The local high school teams -- the San Pedro Pirates -- should be happy. There is some sort of attempt at mixing the pirate genre with the story of a physically or mentally challenged pirate-wannabe, but it kind of fell flat at this level. But the below decks scene was well done.

And finally, there was Steven Spielberg and the Return to Film School. It turns out that Spielberg did drop out of college to take a job as film director early in his career. It is also true that Spielberg went back to California State University Long Beach and got his degree. This film is a fanciful (and comedic) play on a fictionalized Spielberg and his run-ins with film school faculty and his (fictional) fellow students. The actor (Robert W. Laur) and writer/director Josie Hoh have got the right balance between the unlikely event of a billionaire film director coming back to the state university, and the comedic potential of sticking him in filmmaking 101. They play off the use of the Indiana Jones hat quite effectively.

Finally, there was an excerpt of a television show called How to Hack Birth Control. I didn't see all of it, but it has production values, a message, and what looks to be considerable humor. It seems to be designed to drive the right wing into apoplexy. You can catch the trailer here.

There are a few things about these short films that caught my eye. It is a lot cheaper to shoot on modern day video equipment than using film. Apparently, there are a few professional filmmakers who continue to shoot on film, probably because they have mastered that particular skill and don't need to change -- they've already developed careers. But movie theaters have changed over to the digital format, and that's how films get shown. It's also a lot easier to copy film to digital media nowadays.

So in an era where even big budget feature length films are sometimes shot on video media, why do these short films look different (at least to me)? One issue is that most feature length films and television shows have multiple plot elements which are interwoven over the course of 30 minutes or 2 hours. We start out with one plotline (the detectives are looking at the body and have to solve the case) and within moments we will cut away to the second plot line (one of the detectives is having marital problems because his wife is having an affair with another detective, and the two detectives will have to coexist or find some other angry way to settle the problem). And inventive writers and directors will interweave some third plot element or teaser just to feed episodes that may be three shows later. The short films, on the other hand, rarely have more than one bare-bones plot, and often enough they don't even resolve that one.

Another tell that we are looking at a low budget (or as our SPIFF director says, the micro-budget) film is that there is little or no camera movement. We have become used to complex and dramatic camera movements. It's a way of maintaining interest and accentuating emotion. We don't see much of that in these films. Instead, we open on a scene with the character in it, and the camera stays put. This is what existed prior to 1919 (the invention of the rotating head tripod). My guess is that the expensive apparatus that does camera lifts and movements is an unthinkable expense. In any case, we don't see a lot of pans and so forth.

One other element we see and hear a lot in these films. The characters drop the words Shit and Fucking into the dialogue simply as ordinary adjectives. Now there are times when it would be not only appropriate, but necessary to the plot. It might be what somebody says when hearing a gun shot, or at the moment of a crash. In other words, there are moments when such words are natural. But in the case of these films, it seems to be some attempt to show that the character is cool, or uneducated, or just a bit rebellious, but in so doing, the characters come across more as unthinking and uninventive in their own use of language. Shakespeare it isn't.

All in all, a fun weekend with lots of invention and creativity.

(Bob Gelfand writes on science, culture, and politics for CityWatch. He can be reached at amrep535@sbcglobal.net.)