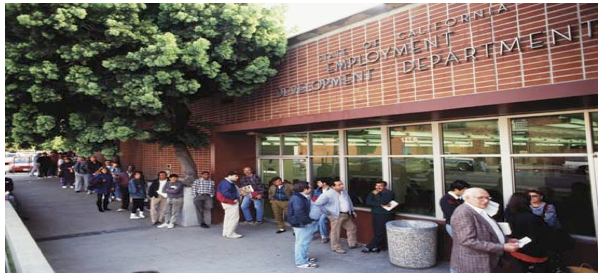

LABOR DAY WORDS - As we approach Labor Day 2013, jobs are scarce. Every job opening attracts more and more applicants, more and more jobs are part-time and low-wage, and fewer and fewer jobs are full-time with benefits. Many adults have given up.

This job landscape is partly due to forces outside the control of policymakers. But much of it is also the result of government policies and political rhetoric over the past decade. What has gone wrong, and how might we bring back full-time hiring?

Scott Hauge has been the owner of CAL Insurance, an independent insurance agency, since 1977. He currently has 28 employees in his business, based in San Francisco’s Sunset District. Since 2005, he has been head of Small Business California, a non-profit business advocacy organization that regularly communicates with more than 5,000 small businesses throughout the state. Recently, he asked those on his e-mail list about their hiring plans for the new 2013-14 fiscal year.

Business owners from across the state wrote about increases in local government fees, higher payroll costs, and, most of all, healthcare costs under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Their answers suggest that we have reached a tipping point against full-time hiring.

One lengthy and thoughtful response came from Henry Marvin of the Marvin Insurance Agency of Lancaster. “The tipping point for clients of mine is 50 employees,” he wrote. “If they are under 50 they don’t want to go over this amount and be subject to ACA fines. The American Family Leave Act is also at 50 employees. I have some employers at 60 employees that are going to lay off employees to go under the 50 limit.”

Marvin noted that the “other tipping point” is reached when an “employee costs an additional 40 percent or more” over his or her salary. When benefits and other costs reach this mark, employers will do anything to avoid to bringing on new people.

The owner of a Bay Area home healthcare business wrote that, while she needed to hire people, her business, and other businesses, were inclined to choose independent contractors. The owner personally preferred to use full-time employees, but she could not do that and stay competitive with those who depend on independent contractors. Other business owners wrote about moving away from full-time hiring because of fear of tax increases. Besides, they had learned to make do with fewer workers during the Great Recession.

Some payroll costs have decreased in the past decade, most notably workers’ compensation, which costs less than half of what it did per $100 of payroll a decade ago. But other costs—including those related to healthcare, federal payroll fees, and federal unemployment insurance mandates—have increased. Also, business owners fear that government, particularly the federal government, will continue to layer on fees and taxes to pay for social benefits and other government programs.

At first glance, the national and state payroll numbers look robust: The nation has gained 6.7 million payroll jobs since February 2010, and California has done even better on a per capita basis, gaining more than 800,000 payroll jobs. But these numbers are misleading. A good number of these jobs are not full-time (in July 2013, 8.3 million workers were involuntarily working part-time). The pace of job generation following the Great Recession is also considerably slower than after previous recessions in the post-World War II period, as detailed in a recent report from the Kauffman Foundation.

Employers look at hiring and see mainly increased costs and challenges, so they have moved toward part-time work and independent contracting.

Businesses are easy targets for politicians. One recent example from San Francisco is the “family-friendly workplace” legislation proposed by Board of Supervisors President David Chiu, who has been looking for a winning issue as he runs for the State Assembly in 2014. In June, Chiu introduced an ordinance granting any employee who is a parent or caregiver the right to request a flexible work schedule—telecommuting, job sharing, working part-time, or adjusting hours. An employer could deny the request only if it would create an “undue hardship,” and the worker could appeal any denial to the city’s Office of Labor Standards Enforcement.

Chiu said he wanted to encourage families to remain in San Francisco, but the proposed ordinance targeted people working in San Francisco, not living in San Francisco. Further, most employers already make work schedule allowances for employees, especially valued employees. Making such schedules into a legal “right” would add whole new layers of legal confrontations and costs—and might even make arrangements less flexible.

Reversing some of the mandates and fees that affect employment is hardly the only strategy to encourage hiring in California and the United States. But it is an essential one. Without a fight against policies that undermine employment, the other strategies for hiring—building infrastructure, education, even creating targeted government jobs programs—will have minimal impact.

This does not mean that all increased employee costs should be opposed. Scott Hauge and Small Business California have supported state minimum wage hikes and increases in workers’ compensation payments to some people with disabilities. But they are able to see these individual costs in the context of many other costs and how they work together. Politicians tend to see any given policy in isolation. When policies that might be defensible on their own stack up, they produce cumulative impacts against hiring.

In Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, her book on the low-wage workforce, author Barbara Ehrenreich describes low-wage workers as “the major philanthropists of our society,” people who “endure privation so that inflation will be low and stock prices high.” A member of the working poor is “an anonymous donor, a nameless benefactor, to everyone else.”

There is considerable truth in Ehrenreich’s argument, but it applies to more than just workers. To be in business and hire employees is to be responsible for paying these employees, whether money comes in or not. It is to be beset by local, state, and government entities demanding money to support their other activities. Today, small and medium-sized businesses have joined low-wage workers as major philanthropists of our society. It’s time we did a better job of helping them to help us.

(Michael Bernick, the former director of the California Employment Development Department, is counsel with the Sedgwick law firm in San Francisco, a research fellow with the Milken Institute, and a consulting editor at Zócalo Public Square … where this article was first posted. Zocalo Public Square … connecting people and ideas.)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 11 Issue 70

Pub: Aug 30, 2013